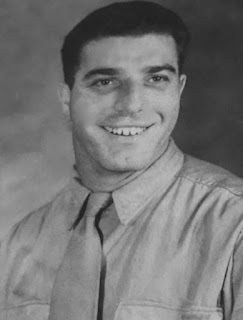

Attilio J. Simone

Rank: Private

Unit: 29th Infantry Regiment, 116th Infantry Regiment, Co. “K”

|

| 147 Shreve St. Mt. Holly, NJ |

It wasn't long before that the Simones migrated to Camden, New Jersey some time prior to 1935. This is where Attilio met his future wife, Caroline Bardolf. On July 2nd, 1938, Atillio and Caroline traveled to Elkton, Maryland, where the couple were wed by Minister J.T. Baker. The newlyweds moved into a house at 969 Florence Street in Camden. At the time of marriage, Attilio was listed as being employed at a wool mill under the Works Progress Administration. He later became a machinist helper at Camden Forge, where his father-in-law was also employed as a crane operator. On April 9, 1939, Attilio and Caroline welcomed the birth of a son, Harry Charles Simone.

The Selective Training and Service Act was enacted on September 16, 1940. This was the first peacetime conscription in U.S. history, requiring men between the ages of 21 and 36 register with their local draft board. Attilio registered on October 16, 1940 with Camden City draft board #12. This particular board was headquartered at the H.B. Wilson Elementary School situated at the intersection of 9th and Florence Street. According to the information on his registration card, he stood at five-foot, eleven inches tall, weighed 152 pounds, had brown eyes, brown hair and a dark complexion. There was also a comment that he had a scar on his left forearm.

|

| 1229th Reception Center, Ft. Dix |

Following the exam, the men returned to the mess hall for lunch. The afternoon was spent marching and formation drills. By 3:30 P.M., the Company was dismissed and returned to the barracks to organize their belongings and report back to the chow hall for dinner at 6:30 P.M. Unfortunate souls would catch the much dreaded “KP” (kitchen patrol) duty. From 7 to 11 P.M., recruits were free to unwind. The routine for day three was much like the previous day. Up at the crack of dawn, and fall into formation. Getting ready for the Army life. After breakfast, the recruits took an IQ test and an interview to determine what job classification each man would be assigned to. They would also sign up for the G.I. life insurance policy which provided $10,000 to a soldier’s beneficiary if the applicant was killed in action. Attilio received orders report to the train station near Fort Dix with other recruits having absolutely no idea of their next destination. This was just another thing these men would learn about the Army.

After a few days of travel, the train stopped at Anniston, Alabama. Attilio disembarked and was transported to Camp McClellan to begin basic training. Camp McClellan was an infantry replacement training center, where new recruits spent about 15 weeks learning how to be a soldier. Private Simone was assigned to an Infantry Training Battalion and spent the first five weeks listening to lectures about military courtesy, sex hygiene, mines and booby traps, first aid for soldiers, map reading, marksmanship and other fundamentals. Let's not forget the marching! Endless miles of hiking; no matter of time or weather. All of the men trudged along with heavy backpacks loaded with their gear. They learned all about the operation of the M-1 “Garand” rifle, the M-1 carbine, the Browning Automatic Rifle (B.A.R), the .30 caliber machine-gun, even a bazooka. Attilio would spend weeks training with all of these weapons and had to take a test at the firing range to qualify on each of them. Simone and the men of the battalion would continue their training in various tactical operational courses on overhead artillery fire training, village fighting, bayonet instruction, and infiltration course (day & night) where all weapons were loaded with live ammunition.

At the completion of basic training, Attilio was granted a 10-day furlough. He took this opportunity to return to Mount Ephraim to see the family, particularly his baby daughter, Dorothy who had been born on September 30th. When his liberty was up, Attilio traveled via train to the Army Ground Force Replacement Depot #1 at Fort George G. Meade in Maryland. This was one of only two Army installations in the country where soldiers gathered to be shipped overseas as replacements for men who had been killed, wounded, reassigned or discharged. Here, the officers made sure these soldiers were adequately prepared. The men were kept active to maintain their mental and physical conditioning sharp. Additional training, weapon proficiency checks, physical examinations, and inoculations were all performed to make sure the troops were fit for overseas duty.

Soldiers would not be granted liberty from the base as their date of embarkation was imminent. In fact, they could not have visitors, make telephone calls, or send letters to family and friends until they got to their next destination. Large movement of troops towards ports had to be conducted in secrecy to prevent alerting foreign agents and possible sabotage acts. Private Simone would later board a train and head to an unknown Port of Embarkation.

The men were temporarily staged at an Army camp anywhere from a day to a few weeks. These camps were strategically located in the vicinity of nearby ports. On their assigned date of departure, the men were transported to the dock where they walked up a gangplank onto the troop ship and would set off later in the day. Just as in the early days of his training, Attilio was not told the destination of the transport.

The ship cruised across the Atlantic Ocean and arrived in the United Kingdom. The troops disembarked and were detailed to a stockage depot for the day. Attilio and his fellow soldiers must have felt like a herd of cattle, being rounded up and moved on from place to place. They would be shuffled off to a “package” area to be placed into a smaller group of replacement soldiers. Within a few days, this group was shipped across the English Channel to La Havre, France and then transported to Givet, Belgium, where they were assigned to the 11th Replacement Depot of the Ground Forces Reinforcement Command. Simone would stay there until being transferred to the 18th Replacement Depot, a direct support depot located in Tonges, Belgium. He would later be sent on to a replacement detachment located just to the rear of the forward troops.

The life of a replacement soldier was said to be one of anxiousness and depression. He could hear the sounds of gunfire and exploding artillery in the distance. Attilio was not yet in the war, but it was getting closer and closer to him. All he could do is await his turn to be called to the front line. The veteran infantrymen didn't take too well to these soldiers. A long-time veteran comrade had been killed or injured and now replaced with an inexperienced stranger. It was believed that the replacements would quickly get themselves killed. This made it very difficult for new soldiers to be accepted by the seasoned men of the units.

|

| 116th Inf. Regiment patch |

The 116th Regiment would stay in this area until March 31st, when they received orders for a pre-dawn move to cross the Rhine River at Rheinberg and stage in Bruckhausen, Germany. Their stay did not last long, as orders were received that afternoon to join up with the 75th Infantry Division in Marl on April 1st. Their objective was to take the city of Dortmund, a key manufacturing area for the German war machine. The 116th spent April 2nd and 3rd marching to the outskirts of the city. On April 4th they seized the town of Waltrop, taking hundreds of German prisoners. The 3rd Battalion of the 116th was held in reserve on April 5th.

The following is an excerpt from "The Last Roll Call: The 29th Infantry Division Victorious, 1945” by Joseph Balkoski. It is a narrative of what happened to the 3rd battalion of the 116th Infantry Regiment on April 6, 1945:

|

| 29th Inf. Div patch |

Led by Capt. Berthier Hawks's Company I, the 3rd Battalion fanned out on the far side of the canal and warily headed south just as the first pink hints of dawn appeared on the eastern horizon. Company K's Lieutenant Easton recalled, “It was a little like attacking New York City. Imagine a long meadow resembling Central Park, but V-shaped, its apex pointing from the suburbs into the heart of downtown.” The 29ers crossed the empty Reichsautobahn at one of its distinctive cloverleaf junctions and headed south, giving the Dortmund suburb of Mengede a wide berth on their right. Unfortunately, that move exposed the battalion's right flank, and according to a report, “The enemy seized the opportunity and began to throw in an increasing volume of artillery.” Also, as Easton related in a letter to his wife, “The German FOs [forward artillery observers] were up in the skyscrapers and had a truly beautiful view of us.”

The 116th's action report remarked that German resistance was “overpowered with a violent barrage from every mortar and artillery piece in the supporting units.” A vital element of that support was provided by Company B, 747th Tank Battalion, and a light tank platoon from Company D, both of which had crossed the canal at the autobahn bridge at dawn, joined up with the dogfaces as they trudged southward, and opened fire with 75-millimeter shells and machine guns on any German who dared to offer resistance. The 747th reported that resistance “ceased as soon as the tanks closed in.”

Puntenney's men pressed on. “We advanced rather grandly if absurdly in a broad skirmish line down the meadow toward the rising sun, dew on the grass, shot and shell flying around,” wrote Easton. “Really it was fantastic, a covey of brown-clothed men scattered over the meadow, those skyscrapers rearing up in front of us like mountain peaks with the sun coming over their summits.” By the end of the day, the 3rd Battalion had gained the three miles stipulated in Bingham's orders and settled in for the night in the Dortmund suburbs of Nette, Nieder, and Ellinghausen, alongside a major rail artery running into Dortmund.

Puntenney paid a high price for that three-mile gain, as during the attack enemy howitzer and mortar fire inflicted thirteen casualties on his outfit, including three dead: two from Company K and one from Company I.

Lieutenant Robert Easton of Company K of the 116th Infantry Regiment wrote a book entitled “Love and War: Pearl Harbor Through V-J Day” containing letters and reflections that he wrote during World War II. The following is a paragraph from this book. It was a letter he wrote to his wife, Jane that directly mentions Attilio and what happened to him in Groppenbruch, Germany on that fateful day:

"Pvt. Attilio Simone of Camden, New Jersey, twenty-seven years old, had been in the Army less than a year and had joined Company K as a replacement only a month ago. At the close of the day, I saw him lying in a plowed field in a drizzle of gray rain. They had laid his poncho over him and marked him with his own rifle, stuck in by the muzzle with his helmet over the butt. He was my man, Janie. I had led him where he was. He was following me. Perhaps the bullet intended for me hit him. If I live a hundred years, the thought of him will never leave me.”

He was originally buried at Plot AA, Row 6, Grave 130 at the U.S. Military Cemetery in Margraten, Holland on April 9, 1945. A temporary wooden cross was erected at the gravesite with one of his dog tags nailed to it for identification purposes. A letter was sent to Caroline stating that her husband had been killed in action in Germany.

On December 2, 1947, the Quartermaster General's office sent a letter to Caroline requesting her disposition of whether to have her husband's remains buried overseas in an American National Cemetery or to return him to the United States to be interred. By the end of September 1948, Caroline completed the paperwork and decided to have Attilio buried with his brothers in arms in Europe. Jennie Simone wanted her son brought back to New Jersey to be laid to rest with his family. Unfortunately, Caroline had the final say since she was listed as next of kin.

By February 10, 1949, Private Attilio J. Simone was buried in Plot L, Row 21, Grave 5 at Netherlands American Cemetery in Margraten, Netherlands. Ever since 1945, a local resident has “adopted” his grave. This is thanks to a Dutch organization known as the Foundation for Adopting Graves at American Cemetery in Margraten. One of their main goals is "to share the stories of the 10,023 American heroes who gave their lives for our freedom, to commemorate them and to cherish the warm and good relationship between the adopting families and the next of kin in the United States of America. It is important that new generations learn from the past and honor the victims of WWII.” Presently, a gentleman by the name of Mr. Erik Kalsbeek in the one who places a flower bouquet at Attilio’s grave marker each year.

|

| Grave marker of Attilio Simone |

Attilio was posthumously awarded the Purple Heart and survived by his wife Caroline, children Harry and Dorothy; parents Joseph and Jennie; siblings Dominico, Vincent, Anthony, Josephine and Peter (who also lived in Mount Ephraim at 16 Lincoln Avenue). All of the Simone boys served in the Army during World War II. It was said by relative Georgette Hawks, that when the Army representatives arrived at the door of Attilio’s parents house to deliver the news of his death, Jennie collapsed onto the floor in grief. Daughter, Dorothy "Dot" was told that her father would bring home roses for her mother. After his death, there were occasions that rose petals would mysteriously appear on the floor in the house.

On a personal note, Attilio Simone was the reason that I started researching the Mount Ephraim veterans that perished during the war. Not only is he honored at the Veterans Triangle on Davis Avenue, but being a member of the Mt. Ephraim Fire Department, we also honor him as he was a member of Fire Company #2. His name is inscribed on the Memorial in front of the firehouse and read on Memorial Day. Every year, I heard the names read aloud but never knew anything about these brave men.

Hopefully the work I have done so far will interest others to know who these men were and go on to let future generations learn about some hometown heroes who perished long before their time. They were much more than just names engraved in stone.

May their sacrifice never be forgotten.

That's my great uncle, who I am even prouder today to hold his name as my middle. The Simone boys true American Heros.

ReplyDelete