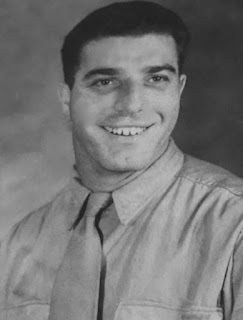

Jerry J. Giordano

Rank: Private First Class

Unit: 4th Infantry Div, 12th Infantry Reg, Co. “G”

|

| 57 W. Kings Hwy, Mt. Ephraim |

As the United States entered World War II, young men from all over the country would register for the draft. Angelo and Jerry would register on October 16, 1940. According to the description of the registrant, Jerry stood at five-foot seven, weighted 150 pounds, had brown eyes, brown hair and a light complexion. After registering for the draft on July 1, 1941, Frank would be the first brother to enter the service on February 24, 1942. He would enlist in the Army at Fort Dix. Next came Angelo, who enlisted in the Army on May 8th. Nick would register for the draft a month later and enlisted in the Army on November 25th. For now, Jerry was not selected to join the military. However, he would not have to wait for too much longer.

A telegram arrived for Jerry in early February 1943 from the Camden County Selective Service Board #3, Gloucester City. His name was chosen during this round and called to serve his country in the armed forces. On the cold and snowy day of the 15th, he would sign enlistment papers at the municipal building located at Broadway and Monmouth Street. After an initial physical exam, it was determined that Jerry had an astigmatism and some dental issues. He was given a classification of 1A (fit for military service). Jerry the rest of the group of selectees, including another future Mount Ephraim fallen soldier, Leslie Holtzapfel were then sworn into the United States Army.

|

| 1229th RC Barracks |

Following the exam, the men returned to the mess hall for lunch. The afternoon was spent marching and formation drills. By 3:30pm, the Company was dismissed and returned to the barracks to organize their belongings and report back for dinner at 6:30pm. Unfortunate souls would catch the much dreaded “KP” (kitchen patrol) duty. From 7 to 11pm, recruits were free to unwind. The routine for day 3 was much like the previous day. Up at the crack of dawn, and fall into formation. Getting ready for the Army life. After breakfast, the recruits took an IQ test and an interview to determine what job classification each man would be assigned to. They would also sign up for the G.I. life insurance policy which provided $10,000 to a soldier’s beneficiary, should the applicant was killed in action. In this case, Jerry designated his mother and father to be his benefactors. On day 4, Jerry found out that he and fellow Mount Ephraim recruit, Leslie Holtzapfel had orders to report to the train depot for destination: unknown. Their stop was found to be Camp Swift in Texas.

|

| 97th Inf. Div. Patch |

Once at Camp Swift, Giordano and Holtzapfel were assigned to the recently reactivated 97th Infantry Division, who were stationed here at the time. The two men completed their basic training and transferred into separate units, although both remained with the 97th Division. Private Giordano would be assigned to the 387th Infantry Regiment, Company “D” and Private Holtzapfel was appointed to the 303rd Field Artillery Battalion, Battery “B.”

Jerry would receive a promotion to Private First Class on October 12, 1943. Later that month, the 97th Division departed Camp Swift to participate in the Louisiana Maneuvers during the fall and winter of 1943-1944. The intense exercises in the bayous, swamplands, and burned-out stump forests of Louisiana increased the stamina of the soldiers and strengthened their military skills. The winter weather was miserable. Sleet, rain, and snow turned dirt roads into quagmires. Christmas services under leaden December skies were long remembered by the soldiers of the Division. The Louisiana Maneuver area served as a proving ground. During those four months, the men of the Division learned to sleep on the ground, live in wet clothes, and value comradeship, but above all, they became tough and proficient soldiers.

|

| Jerry and parents during furlough |

In late April 1944, approximately 5,000 soldiers were "stripped" from the Division while at Fort Leonard Wood. There was a great need for a build-up of troops overseas. The 97th Infantry Division was said to be one of the best trained divisions in the Army at the time. This group was most desirable to the depot because the soldiers had been training for a over a year. Usually, the men transferred into the replacement depot had been sent from an infantry replacement training center, which gave most recruits only a couple of months of initial training. Jerry and Leslie were two of these soldiers who were pulled from the 97th Division and sent to the Army Ground Forces Replacement Depot #1 at Fort George G. Meade in Maryland from April 25 to May 5th. The group was formed into a regiment and assigned to individual companies.

Fort Meade was one of only two Army installations in the country where soldiers gathered to be shipped overseas as replacements for men who had been killed, wounded, reassigned or discharged. Here, the officers made sure these soldiers were adequately prepared. The men were kept active to maintain their mental and physical conditioning sharp. Additional training, weapon proficiency checks, physical examinations, and inoculations were all performed to make sure the troops were fit for overseas duty. Soldiers would not be granted liberty from the base as their date of embarkation was imminent. In fact, they could not have visitors, make telephone calls, or send letters to family and friends until they got to their next destination. Large movement of troops towards ports had to be conducted in secrecy to prevent alerting foreign agents and possible sabotage acts.

|

| soldiers boarding transport ship |

The ship arrived in the United Kingdom on June 27th and the troops disembarked. Jerry was detailed to a stockage depot for a day where he and his fellow soldiers felt they were handled like a herd of cattle. He would then be shuffled off to a “package” area to be placed into a smaller group of replacement soldiers. On June 29th, Jerry was assigned to Detachment 1 of the 15th Replacement Depot in Delamere, England and remain there until July 4th. He wold have to undergo what was known as the “UK Indoctrination Course. This was to familiarize all officers and soldiers of the policies, rules and restrictions in effect for all American forces in the United Kingdom. The next day, Jerry was sent across the English Channel to France. PFC Giordano was re-assigned once again by July 19th, this time to Detachment 51 of the 92nd Replacement Battalion in Fortenay. At this point, Jerry would have been staged just to the rear of the front line troops.

|

| 12th Inf. Reg. Patch |

From 4th Infantry Division Association President, Bob Babcock: "One of the proudest days in the storied history of the 4th Infantry Division came on 25 August 1944 when the division was the first Allied force to enter Paris. History gives credit for the liberation to the French 2nd Armored Division, but our men who were there that day know differently. The 12th Infantry Regiment led the way into Paris, followed by the rest of the 4th Infantry Division.” Jerry Giordano would have been a part of this operation.

The following is the recollection of “Liberation of Paris” from Carlton Stauffer, a fellow member of Company “G," 12th Infantry Regiment:

"At 1900 hours, August 23, 1944, our 12th Regimental Combat Team consisting of the 12th Infantry Regiment, the 38th Cavalry Reconnaissance Squadron, the 42nd Field Artillery Battalion, Company B of the 634th Tank Destroyer Battalion, and Companies B and D of the 70th Tank Battalion, started a motor march, which was to be the most exciting experience I would have during my army career. The mission of our combat team was to seize and hold the bridges over the Seine River in the vicinity of Corbeil, which is approximately twenty-five miles southeast of Paris. As it seemed to be in our usual pattern of things, the weather was dark and stormy. It was another night of skidding off the road into ditches with the usual few Nazi planes overhead. This motor march was in 6x6 trucks with as many fellows as could possibly fit into the cargo area jammed in.

There were fold-down seats along each side, but most of us sat on the floor. To say we were miserable is a gross understatement, with the rain coming down in buckets all night long. Every few hours we stopped to let the men stretch their legs and make the necessary nature calls. I remember one guy in the front part of the cargo space who had very little control and had to relieve himself several times during the night. Naturally, he used his helmet, the all-purpose accessory of the infantryman. As we were moving forward, he had to pass it back to have someone in the rear empty it so as not to blow into the side of the truck body. By morning, all of us were losing patience with the guy and about the only thing to relieve the tension was to curse at him.

As dawn appeared, matters became more tolerable. The rain finally subsided and we saw a new world—gently rolling terrain—the kind we felt would be tank country. Gone were the hedgerows of Normandy. War had moved quickly over this terrain, and there was less evidence of its devastation. As we passed through the small French towns, the townspeople lined the streets and greeted us with enthusiasm, holding flowers and wine up to us. It was only a taste of the celebration that awaited us in Paris. We stopped at a little town named Orphin at about 1030 hours on the morning of August 24.

We let ourselves dry out as we stretched our legs and got some rations. The vehicles were gassed up. We got the word that it would be the honor of the 12th Regimental Combat Team to be the first U.S. troops to enter Paris. We were to support the 2nd French Armored Division, which was given the political role of liberating Paris. To insure that nothing went awry, the Supreme Headquarters, Allied Expeditionary Forces assigned the responsibility to the 12th Infantry to insure a smooth liberation.

We resumed our motor march some time during the afternoon of the 24th, and since we were in the suburbs of Paris, the celebrating was getting into high gear even then. Madly cheering French people wanted our convoy to slow down to give their hands, their flowers, their wine, and their sincere thanks to their liberators. About 0800 hours on the morning of August 25, we began to move into the city of Paris. The details of an acceptable surrender with the Nazis are a matter of history, but we in our six-by-six’s knew nothing of the plans. We all felt an exhilaration that would not be surpassed in the lives of any of us infantrymen.

As we entered the Rue d’Itale, our tactical motor march became a huge victory parade, and our vehicles became covered with flowers. The pent-up emotions of four bitter years under the Nazi yoke suddenly burst into wild celebration, and the great French citizens made us feel that each of us was personally responsible for the liberation of these grateful people. We felt wonderful! The men, women, and children surged against our trucks on all sides, making a four-mile travel to our positions hours long. There were cries of, “Merci! Merci! S’ank you, S’ank you Vive la Amerique!” Hands reached out just to touch the hands of an American soldier. Babies were held up to be kissed. Young girls were everywhere hugging and kissing the GIs. Old French men saluted. Young men vigorously shook hands and patted the GIs on the back.

Finally, late in the afternoon we took up our position for the night. I had the good fortune to be assigned to a chemistry building at a university on the west side of the Seine. We walked into the building and were met by a lady who was determined to make life just wonderful for us. Captain Tallie Crocker, who was our company commander at that time, spread his blanket on the floor. Being an infantryman, he was always getting as close to the ground as possible. The lady immediately took his blankets and spread them out on a sort of couch that looked like an operating table. It was easier to let her do that than to explain anything. When she left, Captain Crocker put his blanket on the floor.

At about this same time, we all heard loud machine gun fire outside the building. I went out with the captain to see what all of the noise was about. In the courtyard outside our building, a Frenchman of their 2nd Armored Division was in a jeep with a .50 caliber machine gun firing away at the corner of a building in the court. Captain Crocker approached the Frenchman and asked what he was firing at. The Frenchman told him there were “Boche” in the building. Captain Crocker tried to convince him there were no Boche in the building. There was no meeting of minds. Finally, the Captain took the Frenchman on a “Boche hunt” through the building, proving once and for all—no Boche. Situation resolved! The girls came back to the jeep and we did more wild riding around Paris. When we went back into the chemistry building, Captain Crocker’s blanket was back on the table.

That evening some of us went for a walk around town, hitting a few places for a celebration drink. The best part of the evening was to return to our chemistry building with its indoor plumbing. At 0930 hours on the morning of August 26, Father Fries, our regimental chaplain, held Mass in the famous Notre Dame Cathedral, the first mass said after the liberation. Joe Dailey and I attended. It was a strange sight for Notre Dame to see us doughboys sitting at Mass with our rifles and battle gear. The problem confronting us at Mass and afterwards was to keep civilians away. There were ten civilians to one soldier. At last, the company commanders told the crowds that the soldiers were tired and needed sleep. Immediately, and with apologies, the civilians left our positions. That evening we were abruptly brought back to the reality of war when at 2330 hours, the Germans launched a heavy aerial bombing. Fortunately, all we encountered were the flashes and the booms—someone else at the distant part of Paris took it all.”

|

| J.D. Salinger and Ernest Hemingway |

After the liberation, the 12th mopped up pockets of enemy resistance and conducted vigorous patrolling while moving northeast through Bois de Vincennes, Claye Souilly and Bios du Roy. September 6, CT 12 rolled through Rocroi, France and into Belgium, approaching its objective of Saint Hubert by the 8th. The 4th Infantry Division then continued its advance eastward to prepare for a coordinated attack on the West Wall. The 12th Regiment began removing unmanned roadblocks on September 11th and crossed the Salm River against enemy fire. By the next evening, the men reached St. Vith, Belgium.

The 12th infantry Regiment would mark September 13th as another day to remember. At 1:30pm, a stone was found, denoting the international boundary between Belgium and Germany. It is said that spit and other forms of excretion were showered upon this marker by the men of the Second Battalion as they passed, showing their extreme disgust for Germany.

On the morning of September 14th, the 12th Infantry Regiment dispatched patrols consisting of platoons from the 1st and 2nd Battalions. The men encountered intermittent artillery and mortar fire. Vehicular and personnel movement was hampered by muddy roads and heavily wooded terrain, but the men had managed to breach the Siegfried Line by that afternoon. The next morning, CT 12 continued its attack to secure a crossing at the Kyll River. As they approached, the Germans unleashed a barrage of artillery, mortar and small arms fire from the woods. The Regiment suffered many casualties but managed to continue the advancement.

The 12th Infantry continued the attack on the September 16th. At 11am, Company “E” had become surrounded by the enemy. They were able to reconnect with the rest of the Regiment by 4pm after an intense fire fight. On the 17th, the 4th Division cleaned up enemy resistance and destroyed pillboxes under some intense artillery fire which was estimated as having doubled from the previous 24 hours. The advance was once again hindered by lousy weather, poor visibility, and a lack of passable roadways.

A mish-mosh of six German Army companies, most of which were SS troops, conducted a counter attack on the 12th Infantry during the morning of September 19th. The enemy shelled the troops with artillery and gunfire from various tracked vehicles. The attack surprised the soldiers and sent them scrambling for cover. For the remainder of September, the men of the 12th continued to mop up enemy pockets of resistance and patrolling the area.

On September 27th, Jerry wrote to his brother Nick, who was also serving in the Army at the time. The letter opened with “Somewhere in Germany.” Jerry said that he in the best of health and was finally able to write. He told Nick that he had gone through Belgium and that the people there treated the U.S. soldiers fine. “They gave the boys plenty to eat and drink.”

Jerry’s battalion (2nd Battalion) was relieved on October 4th by the 9th Infantry Regiment, 2nd Infantry Division. The men of the 12th marched for 12 miles through the rain and thick mud to an assembly area in the vicinity of Holzheim, Germany, arriving at 7:30pm. They would stay here until October 12th. During their time in Holzheim, the men were given some time to rest. There was finally an opportunity to take a shower, attend a USO show and even church services. It was said that the chow was especially good!

The 4th Infantry Division continued active patrolling on October 13th, and under battalion rotation policy, instituted training program with emphasis on tactics in assault of fortified positions, tactics of tank-infantry coordination, use of flame-throwing tanks, and schools for determination of hostile mortar positions. This would be the routine for the remainder of October and into November. From November 2nd to the 4th, companies were rotated to conduct training with emphasis on small unit problems, flame thrower, mine detection, scouting and patrolling. The 12th Infantry continued contact patrolling without encountering the enemy. On November 5th, the 12th Infantry Regiment was relieved by the 9th Infantry Division and the men prepared to move out again to the area of Zweifall under cover of night and the usual rainy conditions.

The 12th arrived on November 6th to relieve the badly battered troops from the 109th Infantry Regiment, 28th Infantry Division. During this time, the 12th Regiment was attached to the 28th Division. Usually, the relief would be done in an assembly area but the men made the swap, unit for unit directly into the trenches and fox holes of the 109th soldiers. By 12:30pm, Company “G” had settled into their position and checked their surroundings, making improvements if necessary. Jerry was located along the Hürtgen-Grosshau Road in an area known as the Hürtgen Forest.

Jerry and the men from the 4th Infantry Division would officially be involved in what is known as the "Battle of Hürtgen Forest." Below are excerpts from "after action" reports of the 4th Infantry Division dated November 8th through the 13th of 1944. They explain the actions the division encountered each day.

|

| Soldiers patrolling in the Hürtgen Forest |

November 8, 1944, marks the beginning of the most epic battle in the long and proud history of the 4th Infantry Division. Most of you have never heard of the Hurtgen Forest. The toughest battle ever fought by the 4th Infantry Division was waged in the Hurtgen Forest in November and the first few days of December of 1944. The 12th Infantry Regiment entered the battle first, followed on 16 November by the rest of the 4ID. - Bob Babcock

8 November 1944 - D+156

The 4th Division was relieved from attachment to V Corps and attached to VII Corps.

The 1st Battalion of the 12th Infantry attacked at 1230 to take a limited objective. Companies B and after C were stopped by machine gun and small arms fire at 1442. The enemy was well dug in and had put in tactical wire covered by its machine guns. Positions were consolidated for the night.

9 November 1944 - D+157

The 12th Infantry remained attached to the 28th Infantry Division. Company K of the 3rd Battalion attacked at 1100, advanced 250 yards and received machine gun fire at 1110. A fire fight occurred at 1144, 400 yards across the line of departure. A counterattack was also repulsed at 1305 and several men from the 109th Infantry Regiment were rescued. Company I moved forward at 1305 on the left, and elements of Company K passed across the enemy tactical wire at 1630 were stopped by heavy enemy fires.

10 November 1944 - D+158

The 12th Infantry remained attached to the 28th Infantry Division until 1900. New attachments were effected. The 1st Battalion moved out at 0630 and attacked at 0700. It advanced 100 to 200 yards when Company F hit a mine field and was forced to withdraw to reorganize. The 3rd Battalion was counterattacked at 1220 by enemy using flame throwers and the 2nd Battalion was also counterattacked at 1300. In both cases, the enemy employed one company. The enemy was repulsed and 38 prisoners were taken.

11 November 1944 - D+159

Our advances were contested stubbornly; the enemy was even counterattacking at every opportunity in strength varying from platoon to company. At least three such counterattacks were preceded by heavy artillery preparation. In addition to the formal counterattacks, the enemy aggressively attempted to infiltrate our line and attack our forces from the rear. Shelling by enemy artillery was constant throughout the period. Tanks and self-propelled guns were seen mostly in the vicinity of Hurtgen.

The 12th Infantry improved positions beginning at 0800 and efforts were made to clean enemy resistance in the rear areas of the 2nd Battalion. Enemy pressure in this area continued throughout the day and resulted in Companies E and G being isolated. The 1st Battalion attacked to reach isolated companies but was stopped by heavy machine guns, small arms and 88 mm fire.

12 November 1944 - D+160

By holding our attempts to advance practically to a standstill, and his thorough employment of mines of all kinds, barbed wire, and blocks of various nature, the enemy found little difficulty in counterattacking fiercely with infantry supported by armor. Continuous shelling by three to four batteries, ranging in caliber from light to medium, made it difficult for our forces to organize a thrust against the enemy.

The 12th Infantry repulsed enemy counterattacks at 0841, 0846, 1020 and 1413. The enemy attack at 1020 consisted of approximately 150 infantrymen and some tanks but was forced to retreat toward Hurtgen at 1203, leaving behind about 90 men isolated from the rest of the Regiment. These were Companies F and G, and the 1st Battalion which had previously attacked and broken through to relieve F and G companies. At the end of the day, the enemy had cut communications and contacts between Combat Team 12 and the isolated group of soldiers.

13 November 1944 - D+161

The 12th Infantry was engaged in fierce fighting in the Hurtgen Forest. Casualties were high and it was necessary to unify all efforts to obtain necessary replacements.

The enemy remained relatively inactive. Its defense was organized along the same front lines from which patrols operated to probe our positions and to determine our strength. Twenty-one shellings were reported by the 4th Infantry Division units. It was estimated that there were three battalions of enemy artillery capable of firing into the sector held by CT 12. Beginning at 0730, isolated companies A, C, F and G, 12th Infantry, initiated a short withdrawal to reestablish contact. By mid-afternoon, while being harassed by small arms and artillery fire, the operation had been completed successfully.

It was a misty and bitterly cold day on November 13th. Companies “F” and “G” attacked back to the line held by the 1st Battalion. They had managed to pull back to the high ground in the rear of the line, receiving badly needed rations and water which they had gone without for some time. After receiving the rations, they went back up to the line feeling much better. During this period, German artillery rained down upon the American soldiers. All supplies and evacuations had to be completed by carrying parties. The casualties among these carrying parties were huge and all available manpower had to be used. This included using cooks who were never being used in that capacity.

It was during this horrific barrage that shrapnel struck Jerry in the left hand and his right elbow, causing a compound fracture of the arm. The most serious of these injuries though was Jerry’s abdomen, which had been pierced through in several places by shell fragments.

He was carried back the the battalion aid station in West Germeter at 6:20pm. Here the medic applied an infection preventing chemical known as sulfa powder into the open wounds and attempted to control any bleeding. His broken arm was wire splinted and a 1/2 gram of morphine was administered to help manage this tremendous pain. Twenty minutes later, Giordano was transported by the 4th Medical Battalion Collection Company B and evacuated from the front to a casualty clearing station where doctors attempt to stabilize his condition. While en route, Jerry was given an additional 1/4 gram of morphine and 2 units of plasma. At 10:15pm, they arrived at clearing station where he was given a dose of penicillin.

Unfortunately, this facility was not adequately equipped to treat the severity of his wounds. Jerry was the loaded into an ambulance and transported to the 1st Hospital Unit of the 51st Field Hospital. The hospital had been set up in a school building in the town of Roetgen, Germany. Giordano was admitted at 11pm and doctors worked diligently through the night and into morning to repair the perforations in his colon. Sadly, Jerry finally succumbed to his injuries at 8:10am on November 14th. He had been sent to the military cemetery for interment later that afternoon.

|

| Jerry Giordano grave marker |

Jerry was survived by his parents, Pasquale and Rose, and brothers Angelo, Frank and Nicholas. All three brothers served in the Army during World War II.

|

| Giordano Brothers in uniform (L to R): Nick, Frank, Angelo. Jerry is in the smaller pic in center. |

The bell in the steeple of Sacred Heart Church in Mt. Ephraim was donated in Jerry’s memory by his parents. It was blessed and dedicated at 8pm on December 8, 1948 by Reverend Monsignor James A. Bulfin, the Rector of the Immaculate Conception Cathedral in Camden. Reverend John P. Fallon, pastor of the Sacred Heart Church accepted the bell in behalf of the parish. Jerry’s brother Angelo and his wife, Connie were the sponsors for the bell which was dedicated to the Blessed Mother of God. This bell was first placed atop of the old church on Black Horse Pike. The bell was later transferred into the steeple of the new church on Kings Highway once it was built.

May their sacrifice never be forgotten.

Wish I had met him! Thank you Jeff for all of your research. Our Ourfamily is grateful for all of your hard work to bring my Uncle’s story to us. We never got to meet him, but thru your story we feel a connection.

ReplyDelete