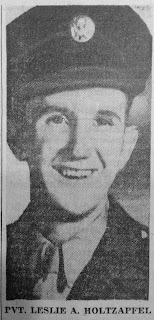

Leslie A. Holtzapfel

Branch: ARMY

Service Number: 32751123

Rank: Private

Unit: 5307th Composite Unit (Provisional), 2nd Battalion, Company “G”

|

| 3119 East Ironsides Road |

Tragedy would strike the Holtzapfel Family once again on February 6, 1931. Roland W. Taylor of Camden was driving his vehicle along Kendall Boulevard in Oaklyn while intoxicated with two passengers; Ms. Alice Little of Camden and Ethel Holtzapfel. At 5:30pm, Taylor entered the intersection at Black Horse Pike when his vehicle sideswiped another car traveling southbound on the pike. The collision left Taylor with a cut above his eye and the back of his head. Alice sustained a broken jaw, some cuts on her left ear and loosened her front teeth. Ethel received the brunt of trauma as the impact threw her against the interior of the vehicle, fracturing her skull. A good samaritan stopped his car at the scene of the accident, loaded up all of the injured and transported them to West Jersey Homeopathic Hospital in Camden. Unfortunately, nothing could be done to revive Ethel, she was pronounced dead on arrival. At the age of nine, Leslie and his siblings were left without a mother.

|

| 13 Davis Avenue |

After the Japanese attacked Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941, young men from all over the country poured into recruitment offices to enlist in every branch of the armed services. The sons of Mount Ephraim were no different. Bud entered in the Army on February 24, 1942. He would be stationed at Camp Tyson in Tennessee for training. Around this time, the Holtzapfels packed up their belongings and changed addresses once again. Albert chose to stay in Mount Ephraim, purchasing a house located across the Black Horse Pike, near Audubon Lake at 13 Valley Road.

Leslie got a job working in the plating department at the Radio Condenser Company on Sheridan Street in Camden, NJ. His sister, Edith and a fellow Mount Ephraim resident, Cornelius Sinon (also later killed during WWII) also were employed here. The company provided radio frequency tuning component parts and sub-assemblies to most of the radio manufacturers as well as the military. Radio Condenser Company is still in business at the same location (Copewood and Thorn Streets) although it is now called “RF Products."

|

| 13 Valley Road |

Leslie arrived at the Gloucester City Hall, located at Broadway and Monmouth Streets, on the morning of February 23th. Gloucester Mayor Albanus Koenemann would preside over a farewell ceremony for the young recruits out in front of the building. The service included remarks and prayers from several local clergymen as well as a few musical selections performed. Before they embarked on their military journey, the church presented each man with a bible and prayer book, while the VFW auxiliary offered them candy and cigarettes.

At the completion of the ceremonies, Leslie boarded a bus which transported him to the 1229th Reception Center at Fort Dix, New Jersey for orientation. During the first day, he was issued his uniform, shoes (size 9 1/2 C) and other necessary gear. He was then assigned to a training company and a barrack to bunk in.

At the completion of the ceremonies, Leslie boarded a bus which transported him to the 1229th Reception Center at Fort Dix, New Jersey for orientation. During the first day, he was issued his uniform, shoes (size 9 1/2 C) and other necessary gear. He was then assigned to a training company and a barrack to bunk in.

Day two, he and the rest of the recruits would be up bright and early at 5:45am for reveille formation. Afterwards they would return to clean up the barracks, shower, shave and report to the mess hall for breakfast at 7am. By 7:30, they were called to detail and each man underwent a physical examination. Here were some of Leslie’s basic attributes at the time: Height: 68 1/2”, Weight: 129 lbs., Eyes: Blue, Hair: Brown.

Following the exam, the men returned to the mess hall for lunch. The afternoon was spent marching and formation drills. A fellow recruit by the name of Paul Allen recalled, “We stood in formation for the first time, trying to look and act like soldiers. A tough old sergeant stood in front of us — and his first words were, ‘You think you’re soldiers?!? You’re SH**! — and this began our training.”

Following the exam, the men returned to the mess hall for lunch. The afternoon was spent marching and formation drills. A fellow recruit by the name of Paul Allen recalled, “We stood in formation for the first time, trying to look and act like soldiers. A tough old sergeant stood in front of us — and his first words were, ‘You think you’re soldiers?!? You’re SH**! — and this began our training.”

By 3:30pm, the Company was dismissed and returned to the barracks to organize their belongings. After the daily flag retreat ceremony, the men would go to the “chow hall” for dinner. Unfortunate souls would catch the much dreaded “KP” (kitchen patrol) duty. From 7 to 11pm, recruits were free to unwind.

The routine for the third day was much like the previous day. Up at the crack of dawn, and fall into formation. Getting ready for the Army life. After breakfast, the recruits took an IQ test and an interview to determine what job classification each man would be assigned to. They would also sign up for the G.I. life insurance policy which provided $10,000 to a soldier’s beneficiary if the applicant was killed in action.

Later that day, February 26th, Leslie received orders to ship out. He report to the train station at Fort Dix with absolutely no idea where he would be heading next. At the station, he and fellow Mt. Ephraim recruit, Jerry Giordano boarded a passenger rail car to transport them off to an Army training camp.

The train wound its way through Burlington County, passing Moorestown, Maple Shade and Pennsauken before crossing the railroad bridge on the Delaware River into Philadelphia. They continued traveling southwest until arriving at their destination on March 1.

|

| 97th Infantry Division Patch |

Camp Swift was located in Bastrop, Texas, just east of Austin. Leslie and Jerry stepped off the rail car as an army band played, "Deep in the Heart of Texas." The two were assigned to the recently reactivated 97th Infantry Division, who happened to be stationed there. They were quartered for the night in barracks while awaiting their assignment to a company for basic training.

The next day, the Mt. Ephraim boys were transferred into separate units within the 97th Division to complete 13 weeks of basic training. Jerry would be assigned to the 387th Infantry Regiment. Leslie was sent to the 303rd Field Artillery Battalion, Battery “B,” under the command of Brigadier General Julien Barnes.

Each man would begin training primarily as an infantryman. They were issued a host of equipment including a steel helmet, field pack and a rifle. The basics consisted of lectures, marches, marksmanship using various weaponry. As the scope of the training increased, men learned how to find their way from place to place using maps, bivouac, pitch tents, dig foxholes, and defend themselves using hand-to-hand combat tactics as well as bayonet drills. By mid-June, Leslie would eventually fulfill the training requirements as an infantryman and move onto his specialized assignment with the artillery.

The 303rd Field Artillery Battalion utilized the M2A1 105mm Howitzer. It required a crew of eight to operate, could fire up to ten rounds per minute and had a range of 12,300 yards. Soldiers appreciated it’s accuracy and powerful punch. The howitzer was flexible enough to provide both direct and indirect fire upon it’s target. Battalion crews trained on all facets of transporting, setting-up/breaking down, loading, ranging and firing the weapon at the artillery range at Camp Swift. They later took their Army Ground Forces firing test at Camp Bowie, Texas. At the beginning of August, Leslie would have had a 10-day furlough. It is unknown at this time where he spent it.

|

| M2A1 105mm Howitzer |

Following the Louisiana Maneuver period, the Division was transferred to Fort Leonard Wood in Missouri where it continued with unit training. While stationed here in February, Leslie was fighting off a nasty cold that he contracted from being out in the harsh winter elements for such a long period of time. His ailment had progressively gotten worse and was admitted to the camp hospital where he spent three days recuperating.

In late April 1944, approximately 5,000 soldiers were "stripped" from the Division while at Fort Leonard Wood. There was a great need for a build-up of troops overseas. The 97th Infantry Division was said to be one of the best trained divisions in the Army at the time. This group was most desirable for replacement depots because the soldiers had been training for over a year. Usually, the men transferred into these depots had been sent from an infantry replacement training center, which gave most recruits only a couple of months of initial training.

Leslie and Jerry were two of these soldiers pulled from the 97th Division and sent to the Army Ground Forces Replacement Depot #1 at Fort Meade in Maryland. The group was formed into a regiment and assigned to individual companies. They were then sent to staging grounds at Camp Patrick Henry in Newport News, Virginia. Here they would await the arrival of a transport ship to take them overseas. Although the two boys from Mount Ephraim had no idea of their next destination, Leslie and Jerry’s similar military paths up to this point would split here in Virginia. Giordano and over half of the 5000 men from the 97th Division were destined for the European Theater of Operations. Holtzapfel and 2,218 other soldiers from the 97th would be heading to the other side of the world. It would be the last time either man stepped foot on American soil.

|

| USS General H.W. Butner |

The next day, the ship moved on to Durban, South Africa, where they joined up with another troop ship and a British escort ship. The journey up to that point had been rather pleasant and calm. However, once the ship entered the Indian Ocean, the seas became extremely rough. The convoy stuck close to the shore, however, the conditions did not improve. The next stop was only a brief one. They sailed up the eastern coast of Africa to the British Colony of Mombasa, Kenya before continuing to India. Finally, after a month at sea, the USS General Butner arrived in Bombay (Mumbai), India on on May 25th.

The soldiers disembarked from the ship and loaded onto railroad "cattle cars." They spent the next 4 days traveling northeast through India to a British military training camp in Ramgarh. The group arrived at the camp in the late morning of May 29th. While this was a facility to train soldiers, the group did not participate in any real training. Some believed they were sent there to prepare Chinese soldiers for combat. The enlisted men were not told what was going on or where hey would be heading. They were organized into a battalion, issued weapons and ammunition, and otherwise spent most of the day trying to escape the sweltering heat. To pass the time, the soldiers played cards, wrote letters home to family and perhaps imbibed in a beer here and there.

|

| C-47 "Skytrain" |

Once airborne, the soldiers were finally told where they were going. They were heading to Burma to reinforce the 5307th Composite Unit (Provisional), code name: "Galahad.” These men were more commonly referred to as “Merrill’s Marauders.” The Marauders were an all-volunteer force of 3000 soldiers lead by Brigadier General Frank Merrill, whose mission was to infiltrate deep into the Japanese held territories in the jungles of Burma (now Myanmar) to disrupt and destroy their supply lines, ultimately reopening the blockaded Burma Road.

|

| Merrill's Marauders |

The Marauders' next mission was to retake the area of Myitkyina (pronounced, Mitch-in-uh), meaning “near the big river” in Burmese. The town of Myitkyina is situated along the western bank of the Irrawaddy River and was strategically important to Allied forces because of it’s various transit links to the rest of the country. Of particular importance was reopening the Ledo Road, an important supply road and capturing an airfield which was being utilized by Japanese fighter planes to intercept Allied cargo planes flying between India and China, over "The Hump."

By the time the Marauders had reached the outskirts of Myitkyina in May, it was the middle of the monsoon season and nearly all the soldiers were suffering from a combination of severe exhaustion, malnutrition, and a host of tropical diseases. Even the group's namesake did not escape unscathed. General Merrill would suffer a heart attack on March 29th and had to hand-off command of the Marauders to Colonel Charles N. Hunter. The fact is they were in dire need of relief with fresh troops but replacements were unfortunately not readily available for deployment. Some soldiers were so worn out that they actually began falling asleep during intense fighting.

|

| Merrill's Marauders Patch |

While the battalion had received their basic training prior to their arrival at Fort Meade, the men had not had any quality time to train together as a group. Almost none of these soldiers had ever received any type of jungle warfare training prior to heading to Burma. Worse yet, some of the men never even held a rifle, let alone used one. The “greenest of green” replacements were sent to Lt. Colonel Daniel Still and a few original Marauders, who quickly whipped the Second Battalion into an organized group.

Two days after their arrival, they were on their way two miles northeast to Mankrin, which they occupied. The river road leading from the north into Mankrin and then Myitkyina was now blocked. Lt. Colonel Still informed Colonel Hunter that he was in position but that if he moved out on the road to pass through a narrow area--with the river on the east and the flooded low ground on the right--he had reason to believe the troops would not follow.

Colonel Hunter ordered him to have his men set up a strong defensive line on either side of the road. From here they could prevent Japanese from leaving or entering the town. Patrol activity could be carried out, as well as a carefully planned and well-executed offensive. All the while, they could hope for a Japanese banzai attack in order to annihilate as many as possible. New Galahad advanced slowly day by day as they worked to knock out strong points. Each day, when the number of wounded sent to the aid stations and the surgical team reached twenty, the day’s activity had to be discontinued.

By June 10, 1944, the 209th and 236th Engineer Combat Battalions were entrenched one mile south of Radahpur across and on either side of the Radahpur- Myitkyina Road. Their blocking line ran about one and a half miles to the west, where the Chinese blocked all western and southern entrances to the city. The Second Battalion of New Galahad defended a line running from the eastern edge of the engineer’s sector northeastward through the town of Mankrin to the Irrawaddy River. The engineers were about two miles from the town, the Second Battalion of Galahad about three miles, and the Chinese forces about two thousand yards. The Siege of Myitkyina began for these replacements troops.

|

| 75mm Pack Howitzer in Myitkyina |

By June 17th, the Second Battalion of Galahad controlled the Maingna Ferry Road and a clear passage to the Irrawaddy River. They were one mile closer to the town than they had been on the 13th. The engineers and the rest of Galahad now also controlled the Myitkyina-Mogaung-Sumprabum road junction. Progress was slow along the Amercians’ front during the rest of June, but small gains were made during most days. Casualties continued to mount--both from battle and disease.

Leslie didn’t realize it, but protecting he and the Marauders from above was a Mount Ephraim fighter pilot by the name of Lt. Charles F. Heil of 611 Delaware Avenue. Stationed with the 88th Fighter Squadron, 80th Fighter Group (also known as the Burma Banshees), Heil flew a Curtis P-40 Warhawk from Assam, India and makeshift airstrips cut out of the dense jungles of Burma. His missions were primarily dive bombing operations, taking out ground-based targets and providing close air support for the Marauders. Lt. Heil said he had to drop bombs within 30 yards of friendly troops as the enemy lines were often in such close proximity to the American infantrymen. At the time, he was flying as many as four missions a day, ranging in length from 20 minutes to three and a half hours. Some of his missions were to strike Japanese positions within 1500 yards of the Myitkyina airstrip he just took off from. Charles went on to command the squadron, completing 207 combat missions in the China-Burma-India Theater during the war.

On June 28, 1944, Private Holtzapfel was reported missing from his company. In an article from the Courier Post, Albert Sr. stated that he had last received a letter from his son some time in August 1944. The Allies finally took control of Myitkyina on August 3, 1944. Five days later, the 5307th consolidated with the 475th Infantry Regiment. This unit would later become what is now the 75th Ranger Regiment. Leslie was still nowhere to be found and was officially listed as "missing in action" on September 8, 1944. Two months later, Leslie’s younger brother Jack enlisted in the Army. He served with the 27th Infantry Division, 105th Infantry Regiment, Company E, where he saw action on the island of Okinawa and was later sent to Japan as part of the occupying force after the war was over.

|

| Harry Norton (L) Howard Auld (R) |

Auld, 25, was a 200 pound, six foot-two inch tall paratrooper who had recently been medically discharged from the service. He attended a party celebrating V-J Day on the evening of August 14th at the Bellmawr Firehouse with a woman named Margaret “Rita” McDade. The two had left the party and walked down Black Horse Pike to Haddon Heights. Auld admitted to beating, and raping the 23 year old waitress from Philadelphia, then throwing her into a cistern at Maple Avenue and the pike. She died as a result of drowning. After a lengthy trial, he was found guilty of his crimes and sentenced to death.

Albert received an interesting letter dated October 23, 1945 from a Lieutenant Louis Hardcastle of Mount Holly, New Jersey. The Lieutenant stated that he had talked to Leslie only a few months earlier in Calcutta, India. He said that Private Holtzapfel was “in native hands and still alive.” Confused, Mr. Holtzapfel contacted the Army about the letter and wanted to know more information about the whereabouts of his son. This was a glimmer of hope. The Army had requested information from their Headquarters in the India-Burma Theater about the matter. On Christmas Eve 1945, a reply was received stating that the name of the officer who had talked to Private Holtzapfel’s father had not been received at their office and correspondence was being returned without any further action.

On March 16, 1946, Leslie was officially declared dead by the War Department under Section 5 of the Missing Persons Act. This states the following: Declared Dead --All persons previously reported as missing or missing in action, who were no longer presumed to be living, and in whose cases a finding of death was made by the Chief of the Casualty Branch, AGO, acting for the Secretary of War, pursuant to Section 5 of the "Missing Persons Act," Public Law 490, 77th Congress, 7 March 1942, as amended. Findings of death were made upon or subsequent to 12 months in a missing or missing in action status, and were withheld so long as the person was presumed to be living. They included the date upon which the death was presumed to have occurred for the purposes of termination of crediting pay and allowances, settlements of accounts, and payments of death gratuities. Such date was never less than a year and a day following the day of expiration of the 12 month period. The declared dead columns in this report include figures for those persons classified as declared dead from a missing in action status only. Persons declared dead from a missing status (other than missing in action) are included in the non-battle death statistics in the death tables, but are not separately identified.

Four days later, Albert attended a meeting of The Relatives of Missing Personnel Committee, held at the Gloucester City Municipal Building. This group was formed by Mrs. Kathryn Dye of Mount Ephraim, who’s son James had also been reported missing during the war. The purpose of the organization was to assist families of missing servicemen by learning how to get as much information from the War Department as possible. Correspondence from the military was often vague and left the families of these missing men frustrated, defeated and upset. All the loved ones wanted to know was, “where’s my son and what are you doing to find him?” Albert did not want to believe that his son was dead. To him, there was just no clear evidence to support the Army’s claim.

The Holtzapfel Family held a memorial service for Leslie on March 31,1946 at the Advent Lutheran Church on East Kings Highway in Mount Ephraim. Just two weeks later, Albert Sr. suffered a massive heart attack and passed away while en route to the hospital. The build-up of tremendous stress from the events that had transpired in just the past month was simply too much for him to take.

Leslie would be awarded a Combat Infantryman Badge and the Purple Heart posthumously. For their accomplishments in Burma, the Marauders were awarded a Distinguished Unit Citation in July 1944. They also have the rare distinction of having each member of the unit receiving the Bronze Star. On October 17, 2020, the "Merrill's Marauders Congressional Gold Medal Act" was signed into law by President Trump. There has not been an official date announced for the presentation as of yet, but Leslie's family would also be eligible to receive this.

A board of American Graves Registration Service officers convened at Calcutta, India on January 9, 1948. They wanted to review and determine if further searches were warranted in the case of missing and deceased personnel. In total, 15 cases — one of which being Leslie Holtzapfel — were 5307th/475th Infantry Regiment soldiers, who were killed during June-August 1944 while participating in the Battle for Myitkyina and the surrounding territory. As far as could be ascertained, the remains of the 15 men had not been recovered by AGRS headquarters. Search & Recovery teams made numerous recoveries from the Myitkyina battlefields and many of those were still unidentified and therefore buried as “Unknowns.”

During December 1947, Search & Recovery teams once again searched the Myitkyina battlefields and recovered more remains, some of these were also “Unknowns.” The opinion of the board was that further attempts for recovery of remains would prove unsuccessful. Unless some of the remains positively referred to the 15 men of the 5307th/475th, they would ultimately be considered non- recoverable remains. The recommendation was that no further attempts for recovery of subject decedents be made and that the remains be declared “non- recoverable.”

In a letter from AGRS India-Burma Zone dated January 20, 1948, stated it was possible that the remains of some of the personnel listed might have been buried as unknowns in the U.S. Military Cemeteries Kalaikunda and Barrackpore, India. All remains that were recovered and previously buried in that zone were sent to Honolulu, Hawaii aboard USAT Albert M. Boe in January 1948. It was recommended that paperwork regarding the missing men be forwarded to the Commanding Officer of AGRS in Honolulu, which would undoubtedly prove helpful during the identifying process.

On February 24,1950, there was a review by the Army concerning the circumstances surrounding the disappearance of Private Leslie A. Holtzapfel. The Quartermaster General Office, Memorial Division reported that a "Non-Recoverable" recommendation from the field was being held, pending further information. They concluded that In the absence of any definite information as to the fate of Private Holtzapfel, and the chance possibility that he might be alive, it was concluded that the information of record in the Department of Army, at that time, did not warrant the issuance of an official report of death.

A “Non-recoverable" case record of review and approval was held on April 18, 1950. The Board of Findings indicated that Search and Recovery Teams had made numerous recoveries from the Myitkyina area and many of these are still unidentified and are buried as “Unknowns.” Due to this information, recommendation of non- recoverability for the deceased was nullified. As a result, OQMG (Office of Quartermaster General) Forms 371 of the deceased were sent to AGRS, Pacific Zone in order that further comparison between the unknowns recovered from Myitkyina and the deceased be made. These forms were compared with negative results, and therefore the original Board findings were re-instated.

A re-examination of records for “Non-recoverable" remains was conducted on May 15, 1951. There was a possible association. A comparison of the dental and physical characteristics of Private Holtzapfel with those of all unknowns recovered from the area of death. However, it failed to establish identity. According to military dental records, Holtzapfel had a full upper and lower plate (dentures), therefore could not be identified by this method.

Private Holtzapfel’s remains most likely lay with the rest of the Unknown soldiers buried at the National Memorial Cemetery of the Pacific in Honolulu, Hawaii. Perhaps one day these graves will be exhumed like the Unknowns of Pearl Harbor have recently been done and can undergo advanced genetic testing so that Leslie’s remains can finally be positively identified. Only time will tell.

Not only is Leslie Holtzapfel’s name engraved on the memorial at the Veterans Triangle on Davis Avenue, in Mount Ephraim, but it is also inscribed on the Walls of the Missing at the Manila American Cemetery in Taguig City, Philippines. He was survived by his brothers Bud and Jack, sisters Hazel Zane and Edith Holtzapfel.

|

| Leslie Holzapfel's name on the Walls of the Missing at Manila American Cemetery |

May their sacrifice never be forgotten.

Comments

Post a Comment