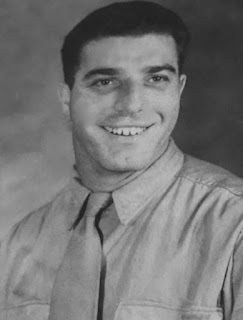

Samuel J. Price

Rank: Technician 5th Grade

Unit: 37th Infantry Division, 117th Combat Engineer Battalion, Co. “C”

Samuel Joseph Price was born November 10, 1918, at 1710 Master Street in Camden, New Jersey to parents William Kirkman Price, Jr., an electrician with the New York Shipbuilding Corporation in Camden and Anna Haug who was a homemaker. He was most likely named after his father’s brother Samuel, a long-time welder at the shipyard. Sam's birth certificate showed that his original birth name was in fact, William Price. He was the youngest of the Price children. Sam had a brother, William “Lester” who was born in 1908 and a sister Anna, born in 1912. The family was residing at 861 Vanhook Street in Camden, NJ according to the 1920 Census. Within the next few years, the Prices would move to 18 Valley Road in Mt. Ephraim, NJ.

Sam attended public school in Mt. Ephraim. He had made the honor roll in February 1925 while in the morning session of first grade. A young Jerry Giordano was also in 1st grade but was in the evening class. Jerry would later lose his life during World War II. On December 16, 1925, the Mt. Ephraim Home & School League (an early version of the Parent Teacher Organization) awarded a prize to the grade with the highest attendance percentage for the month. Sam’s grade (now somehow in third grade) under the tutelage of Ms. Laverson, won for the month of November with 95% attendance.

As a young boy, Sam had taken a liking to art. In April 1929, he found a coloring contest running in the Courier-Post Newpaper. Kids would color a drawing of “Frisco” the Clown which was published for a few days in the newspaper. The 30 “very best” artists would win 2 reserved tickets for the Hagenbeck-Wallace Circus. This would be held at Haddon and Euclid Streets in Camden on April 29, 1929. 10 year-old Sam got right to work, diligently coloring in the black and white clown face to his great satisfaction. He then mailed off his artwork to the Courier, eagerly awaiting the results. Out of more than eleven thousand submissions, Sam’s picture was chosen as one of the “very best” artists. After going to the show, Sam wrote to the Courier-Post thanking them for the tickets:

Dear Editor:—

It is a great pleasure to me to write a story about the circus and let you know how much I enjoyed it. My sister and I started out for the circus and when we got there I wondered how all of the people would get inside of it. But when I got in there, the tent was bigger than I thought. But this was the first time I saw a circus in all of my life. The show was great to see, the horses and elephants and many other animals, but the acrobat and clowns were surely great. The reserved seats we had were just the place I wanted to sit. They couldn’t have been any better, as I saw everything that was going on. And I hope the next time the circus comes to town that I will be there again.

Thank you for the tickets.

Yours truly,

Samuel J. Price

18 Valley Road,

Mt. Ephraim, N.J.

Sam graduated from the Mt. Ephraim School on June 4, 1931 along with 39 other students. The ceremonies were held in the Mt. Ephraim Theatre (later to become the Harwan). More than 1000 parents and relatives were said to have packed the theater to witness the largest graduation class in the borough history at the time. That September, Sam began his freshman year at Audubon High School. While here, he continued to work on his artistic abilities.

In late November, 1932, Sam entered another contest sponsored by the Courier-Post Newspaper. Children age 14 and younger would color the Popeye comic strip that ran in the paper using watercolor paint or crayons. The parents would then mail the artwork to the Courier-Post. On December 1st, Popeye announced all of the winners. Sam ended up as one of twenty fifth-place winners. For his artistic effort, he was awarded with — a flashlight.

While at Audubon, Sam was involved with the school athletic association for all 4 years, although it appears he didn’t participate in any sports. Come senior year, he was appointed as the class Sub-Treasurer, hall monitor, and a member of the “movie benefit” committee.

Maybe most important to him though may have been becoming the art editor for the yearbook, "Le Souvenir." The theme for the year was of old Grecian style. Sam sketched drawings of a writer, a pair of gladiators and wrestlers which appeared on the pages of the book. The write up next to his senior picture described “Sammy” as “Our red-headed artist from Mt. ‘Mud Flats!’ Pictures he’ll paint with swishes and splats.” Written in the yearbook “Prophecy of the Class of 1935,” Sam’s strongest weakness was said to be outlining history, his ambition was to be an aviator, and his inevitable end — a cartoonist.

On the evening of June 13, 1935, 80 boys and 66 girls adorned in cap and gown, walked across the auditorium stage at Audubon High School. Among them was Sam, proudly receiving his diploma.

By 1940, the Great Depression crisis had started to take a turn for the better and people began getting back to work. Sam, however, was unemployed and out looking for jobs. While both of his siblings had already “left the nest,” he was still living with his parents.

On October 16th, Sam was required to register with the Gloucester City draft board under the Selective Training and Service Act. According to the information on his registration card, he stood at six-foot tall, weighed 165 pounds, had blue eyes, red hair and a ruddy complexion. By this time, Sam had been working for Howard Ayars of 14 East Buckingham Avenue. Mr. Ayars was a wallpaper hanger and interior decorator. Sam would assist him by painting houses and tackling other odd jobs. His draft number would not be called until May 1941.

As a young boy, Sam had taken a liking to art. In April 1929, he found a coloring contest running in the Courier-Post Newpaper. Kids would color a drawing of “Frisco” the Clown which was published for a few days in the newspaper. The 30 “very best” artists would win 2 reserved tickets for the Hagenbeck-Wallace Circus. This would be held at Haddon and Euclid Streets in Camden on April 29, 1929. 10 year-old Sam got right to work, diligently coloring in the black and white clown face to his great satisfaction. He then mailed off his artwork to the Courier, eagerly awaiting the results. Out of more than eleven thousand submissions, Sam’s picture was chosen as one of the “very best” artists. After going to the show, Sam wrote to the Courier-Post thanking them for the tickets:

Dear Editor:—

It is a great pleasure to me to write a story about the circus and let you know how much I enjoyed it. My sister and I started out for the circus and when we got there I wondered how all of the people would get inside of it. But when I got in there, the tent was bigger than I thought. But this was the first time I saw a circus in all of my life. The show was great to see, the horses and elephants and many other animals, but the acrobat and clowns were surely great. The reserved seats we had were just the place I wanted to sit. They couldn’t have been any better, as I saw everything that was going on. And I hope the next time the circus comes to town that I will be there again.

Thank you for the tickets.

Yours truly,

Samuel J. Price

18 Valley Road,

Mt. Ephraim, N.J.

Sam graduated from the Mt. Ephraim School on June 4, 1931 along with 39 other students. The ceremonies were held in the Mt. Ephraim Theatre (later to become the Harwan). More than 1000 parents and relatives were said to have packed the theater to witness the largest graduation class in the borough history at the time. That September, Sam began his freshman year at Audubon High School. While here, he continued to work on his artistic abilities.

In late November, 1932, Sam entered another contest sponsored by the Courier-Post Newspaper. Children age 14 and younger would color the Popeye comic strip that ran in the paper using watercolor paint or crayons. The parents would then mail the artwork to the Courier-Post. On December 1st, Popeye announced all of the winners. Sam ended up as one of twenty fifth-place winners. For his artistic effort, he was awarded with — a flashlight.

While at Audubon, Sam was involved with the school athletic association for all 4 years, although it appears he didn’t participate in any sports. Come senior year, he was appointed as the class Sub-Treasurer, hall monitor, and a member of the “movie benefit” committee.

|

| Sam's Yearbook Art |

Maybe most important to him though may have been becoming the art editor for the yearbook, "Le Souvenir." The theme for the year was of old Grecian style. Sam sketched drawings of a writer, a pair of gladiators and wrestlers which appeared on the pages of the book. The write up next to his senior picture described “Sammy” as “Our red-headed artist from Mt. ‘Mud Flats!’ Pictures he’ll paint with swishes and splats.” Written in the yearbook “Prophecy of the Class of 1935,” Sam’s strongest weakness was said to be outlining history, his ambition was to be an aviator, and his inevitable end — a cartoonist.

On the evening of June 13, 1935, 80 boys and 66 girls adorned in cap and gown, walked across the auditorium stage at Audubon High School. Among them was Sam, proudly receiving his diploma.

By 1940, the Great Depression crisis had started to take a turn for the better and people began getting back to work. Sam, however, was unemployed and out looking for jobs. While both of his siblings had already “left the nest,” he was still living with his parents.

On October 16th, Sam was required to register with the Gloucester City draft board under the Selective Training and Service Act. According to the information on his registration card, he stood at six-foot tall, weighed 165 pounds, had blue eyes, red hair and a ruddy complexion. By this time, Sam had been working for Howard Ayars of 14 East Buckingham Avenue. Mr. Ayars was a wallpaper hanger and interior decorator. Sam would assist him by painting houses and tackling other odd jobs. His draft number would not be called until May 1941.

Sam reported to the Gloucester City Municipal Building at 7am on May 5, 1941. He and a group of local selectees boarded a bus which took them up to the induction station at the Trenton Armory. After a physical examination, he was accepted for military service and taken to the Reception Center at Fort Dix for army induction training. Here, he was administered a series of inoculation shots, issued uniforms, footwear and other articles of clothing. Sam was also tested and interviewed for job classification. His enlistment record revealed he had a background as a skilled painter with some construction and maintenance experience. After a little more than a week at Fort Dix, Sam received orders to report to the train station near camp. It was time to ship out. He and other recruits hopped aboard the passenger rail car and departed for an unknown destination.

The train arrived on May 15th at a depot just a few miles southeast of Hattiesburg, Mississippi. The place was an Army training facility by the name of Camp Shelby. Here, the selectees disembarked, and awaited processing which placed them into individual companies. Sam was assigned to Company “B” of the 42nd Engineer Regiment.

Combat engineers are soldiers who are trained to perform construction, repair and demolition tasks in combat environments. Typically, a combat engineer is also trained as an infantryman. They often have a secondary role fighting as infantry when needed.

Two other Mount Ephraimites drafted on May 5th, Elmer Allchin and Earl Faust, were among the recruits who made the journey south by train and were assigned to this outfit, although it is not known if they were in the same company as Sam.

The 42nd Engineer Regiment (General Service) was a newly formed, non-divisional unit at Camp Shelby, commanded by Colonel Bernard Smith. They quickly needed bodies to fill their ranks. At the time, the acquisition of recruits for recently formed Army units was usually from a particular state or region, but smaller groups would eventually arrive from other states. A group of over 1100 selectees with some prior background in construction and/or maintenance were pulled from Fort Dix, making this unit overwhelming compromised of men from New Jersey and New York.

As recruits filtered down to Camp Shelby during the week of May 14-19, the Non-Commissioned Officers (NCOs) kept those who had already arrived quite busy by marching, physical fitness routines, lectures, and various other work details to get this newly built unit area in shape.

The 42nd Engineers came together and began a roughly 13-week basic training period. The recruits were taught a wide range of subjects to make them fully functional soldiers. Lecture subjects included: military courtesy and discipline, Articles of War (military law), sanitation and hygiene, first aid, chemical attack defense, marching, guard duty, hasty field fortifications and bivouacs, camouflage, elementary map and aerial photo reading, and protection of military information.

A great deal of time was spent on the rifles, including assembly and disassembly, care and cleaning, basic marksmanship, firing positions, sighting, range estimation, and range firing. This included zeroing the rifle (adjusting the sights to align with the bullet’s trajectory), firing on known distance ranges, and for qualification. Soldiers would be awarded the Marksman, Sharpshooter, and Expert Badge depending on their qualification score. They learned about the carbine, hand and rifle grenades, landmines, and booby traps.

Daily regiments of physical fitness training was also mandatory for the soldiers. They became intimately familiar with calisthenics known as the Army’s “daily dozen”: jumping jacks, pushups, sit-ups, cherry pickers, rowing exercise, side bends, flutter kicks, toe touches, trunk twisters, in-place double-time, standing leg lifts and lying leg lifts. Training schedules frequently included runs of up to five miles in formation, forced marches of even greater distances with equipment, and obstacle courses. In the field they dug foxholes and had to refill them before displacing. Bayonet training was given more for instilling aggressiveness, coordination, agility, and physical conditioning than the possibility that they might use cold steel in combat.

Basic training included training soldiers in their specialties. Much of this training was done collectively. For example, an engineer squad contained six different specialties in addition to the leader and assistant leader. The bridge carpenters, general carpenters, electricians, drivers, demolition men, jackhammer operators, utility repairmen, and general riggers (specialized in lifting and moving large or heavy objects with block and tackle) within a company would be collected together and provided training. Often, after being given a manual to study, a civilian-experienced jackhammer operator or electrician would find himself training his fellow specialists. Once they had learned the basics of their jobs they learned more about working and training as part of their platoon.

As training progressed they undertook basic squad and platoon movement formations, defensive and offensive tactics, tactical live-fire exercises, and practiced defense against air attack. Engineer specific training included the use of engineer tools, rigging, placing and removing landmines, demolitions, road repair and maintenance, obstacle construction, booby traps, route and bridge reconnaissance, and fixed and floating bridge construction and repair. Regardless of the specialties assigned to individuals within squads they were cross-trained to some degree in all skills. Demolition training was especially popular, although there was a considerable amount of danger involved. They blew up bridges they had built in training, blew down trees, blew stumps out of the ground, cratered roads (and repaired them), cut railroad rails and pipe.

One article found in a local newspaper reported an incident that involved Company “B,” 42nd Engineers on the evening Friday, June 13, 1941:

Scarred ground back of the motor pool of the 42nd Engineers, was the only evidence remaining today of a dynamite blast which Friday night shook every building at Camp Shelby. Crowded service clubs were evacuated instantly, thousands of soldiers dashed from tents into the streets, ambulance drivers prepared for emergency runs, and firemen leaped to the wheels of their trucks as a dense cloud of black smoke rose skyward in the motor pool area.

A quick check by MP and other camp authorities revealed, however, there was no cause for alarm. There were no casualties or damage, and that the explosion, except its severity, was no surprise to the 42nd Engineers. “It was not unexpected,” said Lt. L.H. Ferrier, Company B, 42nd Engineers. “The rule is that any dynamite left over at the end of a day’s work be either destroyed or returned to the magazine house. We had about a half case of dynamite when we finished for this afternoon. It was a mile and a half or two miles to the magazine house, and we had to get to the parade. One of the lieutenants was told to take the dynamite back the lot and set it off. That’s all there was to it.”

Several hundred soldiers were witnessing a British war film, “Night Trains” in one the the camp theaters when the explosion occurred. “We thought the Germans had started bombing us when we heard the detonation,” said one private as he emerged from the theater.

Unit training came next. Platoons worked together with the rest of the company and in turn, the entire regiment to accomplish their mission. Much of the instruction during this time dealt with bridge building. They would team up with different types of bridge companies and learn how to erect bridges day and night regardless of the weather conditions. Vehicles had to be able to safely enter and exit the bridge site and a route had to be available to use as a road. The engineers became problem solvers, reconnoitering possible sites to construct a crossing. If proper conditions were not found, considerable preparatory work had to be undertaken.

The next phase of training would be combined training. The engineer battalion would train alongside other divisional units and performing tasks in support of them as they undertook their own training. Battalion elements would conduct route and bridge reconnaissance, erect bridges, lay and clear inert mines, and construct roads and supply trails. Squad, platoon, and company tactical training was accomplished, which included urban combat exercises. Some of this combined training was put on hold until late summer.

The 42nd Engineer Regiment was issued orders on July 9th to pack up their equipment and prepare to move out to Lake Charles in Louisiana for participation in a series of large-scale field exercises known as the Louisiana Maneuvers. The unit was assigned to operate under the headquarters of Third Army, commanded by General Walter Krueger.

By the morning of July 17th, some 20 army trucks carrying troops and equipment of the 42nd Engineers departed Camp Shelby and headed for Lake Charles, passing through Slidell, Baton Rouge and Crowley. This convoy accounted for only half of the outfit. A second caravan left Camp Shelby on July 28th with 800 more engineers. They traveled south through Mississippi to Slidell, then onto Baton Rouge where the engineers stayed overnight. The next day, they continued to Lafayette then took a different route than the first convoy. This contingence instead went north to Opelousas and then west through Eunice. The reason for this travel separation was a prevention of traffic congestion on any one particular highway as many Army personnel were also en route to participate in the Louisiana Maneuvers.

With the entire regiment now in Lake Charles, they were assigned the mission of land surveying, repairing roadways, and in general, making ready for the upcoming exercises. In the coming days and weeks, the unit would be split up and staged in East Texas, a wooded area outside of Opelousas, Louisiana and at the airport in Eunice until the maneuvers began. From here, the engineers could deploy when needed and would return to the “battlefield” afterwards to repair any damage that was caused.

By the beginning of September, some of the engineers got a much-needed break from the action as they arrived in Bunkie, Louisiana for a few days. The soldiers were tired, wet and hungry after working endlessly in the mud and rain. They were finally able to get a hot shower, write to loved ones and unwind at a dance and variety show in the local USO hut. After a stay of five days in Bunkie, the 42nd Engineers pulled up their tents and went on their way. From the Captain down they had nothing but praise for the way the citizens of this city treated them. They hated to leave, but the call to duty carried them to other locations. The people of the town wished the soldiers Godspeed and good luck.

The regiment returned to Camp Shelby in late September and continued with their training under the Fifth Army Corp. One member, Private Paul V. Moser, wrote to the editor of his hometown newspaper in Connellsville, Pennsylvania about his experiences thus far:

My outfit is the 42nd Engineers, a combination of infantry training, engineering problems and light-hearted, high spirited boys presenting a cross-section of America. We left Camp Shelby for Lake Charles, LA on July 28 to prepare a great area for those great maneuvers. Our work consisted of every type of engineering problem, from a 350-foot, 16 span highway bridge built in four and one-half days, 24-hours a day, by our Company “A” and “B”, to roads, barricades, water points, pontoon bridges and the many camp sites used by various regiments.

Through deep, sticky mud and quicksands of those swamps that cover Louisiana, all of the boys trudged and worked--returning from the different jobs to pup tents floored with water and drenched with rain, sleeping and eating in soaked clothes for days on end, never once quelled the high spirits of a single man. Each took every trial and hardship, wanting more to try to keep ahead of the rest.

I can remember one night near the end of the games. We had been out the entire day and night before, scouting for Red Army parachutists and again we were scouring the swamps and rice bogs for those elusive troopers. There wasn’t one who wasn’t tired, hungry and wet, but when one small fellow, scarcely taller than a full field pack broke his ankle in a fall from the canal wall, everyone took turns in carrying him back to our main group.

Today we may not have a full amount of guns, tanks and planes, but we do have the morale and high-spirits that will never be topped by Hitler and his cronies and soon, when we are fully equipped, those so-called totalitarian world rulers will stand face to face with an army of men ready and willing to fight for their homes and this wonderful country of ours. Today, although we are back in our comfortable tents at Camp Shelby, we are ready to undergo whatever may be asked of us. I know that I speak for every soldier serving today when I say that there will never be a single flaw in this Army of the U.S.

On December 7, 1941, everyone in camp heard the scuttlebutt about the Japanese attacking U.S. forces at Pearl Harbor and other military installations on the Hawaiian Island of Oahu. The following day, the men crowded around the radio in the mess hall, listening to President Roosevelt ask Congress for a Declaration of War. The regimental training would continue with a paramount sense of importance now that their skills would soon be put into action.

Christmas Eve 1941: It is said that the soldiers of the 42nd Engineers sang carols at Camp Shelby on this night. Being away from home during the holidays was rough for them, but they made the most of the situation. Mess halls for each company had a specially prepared Christmas dinner arranged. The men could also find the hospitality at open houses of the 37th, 38th Division and Non-Divisional Service clubs.”

Some time in late December, (rank, Private) Sam was transferred to the newly formed 469th Engineer Shop Company. The soldiers in this unit were trained to repair and maintain all power-driven equipment (water pumps, air compressors, electric generators, earth moving machinery, etc.) used by engineering companies. Machinists, welders and electricians would learn to make or rebuild roughly forty percent of the individual parts used by the repairmen. This shop manufacturing effected a speedy replacement of parts that were often not readily available. During his brief time in this company, Sam was promoted to Private First-Class.

The train arrived on May 15th at a depot just a few miles southeast of Hattiesburg, Mississippi. The place was an Army training facility by the name of Camp Shelby. Here, the selectees disembarked, and awaited processing which placed them into individual companies. Sam was assigned to Company “B” of the 42nd Engineer Regiment.

Combat engineers are soldiers who are trained to perform construction, repair and demolition tasks in combat environments. Typically, a combat engineer is also trained as an infantryman. They often have a secondary role fighting as infantry when needed.

Two other Mount Ephraimites drafted on May 5th, Elmer Allchin and Earl Faust, were among the recruits who made the journey south by train and were assigned to this outfit, although it is not known if they were in the same company as Sam.

The 42nd Engineer Regiment (General Service) was a newly formed, non-divisional unit at Camp Shelby, commanded by Colonel Bernard Smith. They quickly needed bodies to fill their ranks. At the time, the acquisition of recruits for recently formed Army units was usually from a particular state or region, but smaller groups would eventually arrive from other states. A group of over 1100 selectees with some prior background in construction and/or maintenance were pulled from Fort Dix, making this unit overwhelming compromised of men from New Jersey and New York.

As recruits filtered down to Camp Shelby during the week of May 14-19, the Non-Commissioned Officers (NCOs) kept those who had already arrived quite busy by marching, physical fitness routines, lectures, and various other work details to get this newly built unit area in shape.

The 42nd Engineers came together and began a roughly 13-week basic training period. The recruits were taught a wide range of subjects to make them fully functional soldiers. Lecture subjects included: military courtesy and discipline, Articles of War (military law), sanitation and hygiene, first aid, chemical attack defense, marching, guard duty, hasty field fortifications and bivouacs, camouflage, elementary map and aerial photo reading, and protection of military information.

A great deal of time was spent on the rifles, including assembly and disassembly, care and cleaning, basic marksmanship, firing positions, sighting, range estimation, and range firing. This included zeroing the rifle (adjusting the sights to align with the bullet’s trajectory), firing on known distance ranges, and for qualification. Soldiers would be awarded the Marksman, Sharpshooter, and Expert Badge depending on their qualification score. They learned about the carbine, hand and rifle grenades, landmines, and booby traps.

Daily regiments of physical fitness training was also mandatory for the soldiers. They became intimately familiar with calisthenics known as the Army’s “daily dozen”: jumping jacks, pushups, sit-ups, cherry pickers, rowing exercise, side bends, flutter kicks, toe touches, trunk twisters, in-place double-time, standing leg lifts and lying leg lifts. Training schedules frequently included runs of up to five miles in formation, forced marches of even greater distances with equipment, and obstacle courses. In the field they dug foxholes and had to refill them before displacing. Bayonet training was given more for instilling aggressiveness, coordination, agility, and physical conditioning than the possibility that they might use cold steel in combat.

Basic training included training soldiers in their specialties. Much of this training was done collectively. For example, an engineer squad contained six different specialties in addition to the leader and assistant leader. The bridge carpenters, general carpenters, electricians, drivers, demolition men, jackhammer operators, utility repairmen, and general riggers (specialized in lifting and moving large or heavy objects with block and tackle) within a company would be collected together and provided training. Often, after being given a manual to study, a civilian-experienced jackhammer operator or electrician would find himself training his fellow specialists. Once they had learned the basics of their jobs they learned more about working and training as part of their platoon.

As training progressed they undertook basic squad and platoon movement formations, defensive and offensive tactics, tactical live-fire exercises, and practiced defense against air attack. Engineer specific training included the use of engineer tools, rigging, placing and removing landmines, demolitions, road repair and maintenance, obstacle construction, booby traps, route and bridge reconnaissance, and fixed and floating bridge construction and repair. Regardless of the specialties assigned to individuals within squads they were cross-trained to some degree in all skills. Demolition training was especially popular, although there was a considerable amount of danger involved. They blew up bridges they had built in training, blew down trees, blew stumps out of the ground, cratered roads (and repaired them), cut railroad rails and pipe.

One article found in a local newspaper reported an incident that involved Company “B,” 42nd Engineers on the evening Friday, June 13, 1941:

Scarred ground back of the motor pool of the 42nd Engineers, was the only evidence remaining today of a dynamite blast which Friday night shook every building at Camp Shelby. Crowded service clubs were evacuated instantly, thousands of soldiers dashed from tents into the streets, ambulance drivers prepared for emergency runs, and firemen leaped to the wheels of their trucks as a dense cloud of black smoke rose skyward in the motor pool area.

A quick check by MP and other camp authorities revealed, however, there was no cause for alarm. There were no casualties or damage, and that the explosion, except its severity, was no surprise to the 42nd Engineers. “It was not unexpected,” said Lt. L.H. Ferrier, Company B, 42nd Engineers. “The rule is that any dynamite left over at the end of a day’s work be either destroyed or returned to the magazine house. We had about a half case of dynamite when we finished for this afternoon. It was a mile and a half or two miles to the magazine house, and we had to get to the parade. One of the lieutenants was told to take the dynamite back the lot and set it off. That’s all there was to it.”

Several hundred soldiers were witnessing a British war film, “Night Trains” in one the the camp theaters when the explosion occurred. “We thought the Germans had started bombing us when we heard the detonation,” said one private as he emerged from the theater.

Unit training came next. Platoons worked together with the rest of the company and in turn, the entire regiment to accomplish their mission. Much of the instruction during this time dealt with bridge building. They would team up with different types of bridge companies and learn how to erect bridges day and night regardless of the weather conditions. Vehicles had to be able to safely enter and exit the bridge site and a route had to be available to use as a road. The engineers became problem solvers, reconnoitering possible sites to construct a crossing. If proper conditions were not found, considerable preparatory work had to be undertaken.

The next phase of training would be combined training. The engineer battalion would train alongside other divisional units and performing tasks in support of them as they undertook their own training. Battalion elements would conduct route and bridge reconnaissance, erect bridges, lay and clear inert mines, and construct roads and supply trails. Squad, platoon, and company tactical training was accomplished, which included urban combat exercises. Some of this combined training was put on hold until late summer.

The 42nd Engineer Regiment was issued orders on July 9th to pack up their equipment and prepare to move out to Lake Charles in Louisiana for participation in a series of large-scale field exercises known as the Louisiana Maneuvers. The unit was assigned to operate under the headquarters of Third Army, commanded by General Walter Krueger.

By the morning of July 17th, some 20 army trucks carrying troops and equipment of the 42nd Engineers departed Camp Shelby and headed for Lake Charles, passing through Slidell, Baton Rouge and Crowley. This convoy accounted for only half of the outfit. A second caravan left Camp Shelby on July 28th with 800 more engineers. They traveled south through Mississippi to Slidell, then onto Baton Rouge where the engineers stayed overnight. The next day, they continued to Lafayette then took a different route than the first convoy. This contingence instead went north to Opelousas and then west through Eunice. The reason for this travel separation was a prevention of traffic congestion on any one particular highway as many Army personnel were also en route to participate in the Louisiana Maneuvers.

With the entire regiment now in Lake Charles, they were assigned the mission of land surveying, repairing roadways, and in general, making ready for the upcoming exercises. In the coming days and weeks, the unit would be split up and staged in East Texas, a wooded area outside of Opelousas, Louisiana and at the airport in Eunice until the maneuvers began. From here, the engineers could deploy when needed and would return to the “battlefield” afterwards to repair any damage that was caused.

By the beginning of September, some of the engineers got a much-needed break from the action as they arrived in Bunkie, Louisiana for a few days. The soldiers were tired, wet and hungry after working endlessly in the mud and rain. They were finally able to get a hot shower, write to loved ones and unwind at a dance and variety show in the local USO hut. After a stay of five days in Bunkie, the 42nd Engineers pulled up their tents and went on their way. From the Captain down they had nothing but praise for the way the citizens of this city treated them. They hated to leave, but the call to duty carried them to other locations. The people of the town wished the soldiers Godspeed and good luck.

The regiment returned to Camp Shelby in late September and continued with their training under the Fifth Army Corp. One member, Private Paul V. Moser, wrote to the editor of his hometown newspaper in Connellsville, Pennsylvania about his experiences thus far:

My outfit is the 42nd Engineers, a combination of infantry training, engineering problems and light-hearted, high spirited boys presenting a cross-section of America. We left Camp Shelby for Lake Charles, LA on July 28 to prepare a great area for those great maneuvers. Our work consisted of every type of engineering problem, from a 350-foot, 16 span highway bridge built in four and one-half days, 24-hours a day, by our Company “A” and “B”, to roads, barricades, water points, pontoon bridges and the many camp sites used by various regiments.

Through deep, sticky mud and quicksands of those swamps that cover Louisiana, all of the boys trudged and worked--returning from the different jobs to pup tents floored with water and drenched with rain, sleeping and eating in soaked clothes for days on end, never once quelled the high spirits of a single man. Each took every trial and hardship, wanting more to try to keep ahead of the rest.

I can remember one night near the end of the games. We had been out the entire day and night before, scouting for Red Army parachutists and again we were scouring the swamps and rice bogs for those elusive troopers. There wasn’t one who wasn’t tired, hungry and wet, but when one small fellow, scarcely taller than a full field pack broke his ankle in a fall from the canal wall, everyone took turns in carrying him back to our main group.

Today we may not have a full amount of guns, tanks and planes, but we do have the morale and high-spirits that will never be topped by Hitler and his cronies and soon, when we are fully equipped, those so-called totalitarian world rulers will stand face to face with an army of men ready and willing to fight for their homes and this wonderful country of ours. Today, although we are back in our comfortable tents at Camp Shelby, we are ready to undergo whatever may be asked of us. I know that I speak for every soldier serving today when I say that there will never be a single flaw in this Army of the U.S.

On December 7, 1941, everyone in camp heard the scuttlebutt about the Japanese attacking U.S. forces at Pearl Harbor and other military installations on the Hawaiian Island of Oahu. The following day, the men crowded around the radio in the mess hall, listening to President Roosevelt ask Congress for a Declaration of War. The regimental training would continue with a paramount sense of importance now that their skills would soon be put into action.

Christmas Eve 1941: It is said that the soldiers of the 42nd Engineers sang carols at Camp Shelby on this night. Being away from home during the holidays was rough for them, but they made the most of the situation. Mess halls for each company had a specially prepared Christmas dinner arranged. The men could also find the hospitality at open houses of the 37th, 38th Division and Non-Divisional Service clubs.”

Some time in late December, (rank, Private) Sam was transferred to the newly formed 469th Engineer Shop Company. The soldiers in this unit were trained to repair and maintain all power-driven equipment (water pumps, air compressors, electric generators, earth moving machinery, etc.) used by engineering companies. Machinists, welders and electricians would learn to make or rebuild roughly forty percent of the individual parts used by the repairmen. This shop manufacturing effected a speedy replacement of parts that were often not readily available. During his brief time in this company, Sam was promoted to Private First-Class.

On January 28, 1942, he was transferred from the 469th Engineer Shop Company to the 112th Combat Engineer Regiment. This unit was also stationed at Camp Shelby at the time. The 112th Engineers were an element of the 37th Infantry Division. This division was formed from the soldiers of the Ohio National Guardsmen and hence nicknamed the “Buckeye” Division.

Two days after Sam joined this outfit, the regiment was reorganized into a battalion. Personnel were split up and dispersed into smaller groups. The former 1st Battalion had been sent off ahead of the rest for deployment to England back on December 31st. The former 2nd Battalion, still at Camp Shelby, was transferred into the 191th Engineer Battalion (Light Pontoon) with the exception of one platoon (roughly 40 men) from each of Companies D, E and F. These three platoons would be meant to fill-in for the men of the departed 1st Battalion. Sam was assigned to the platoon from Company “F” that would remain with the 112th Engineers.

The 37th Infantry Division received orders on February 3, 1942 to move to the staging area at Indiantown Gap Military Reservation near Harrisburg, Pennsylvania. 112th Engineers arrived at the facility on February 14th.

Orders were changed and the 37th was diverted for service from the European Theater to the Pacific Theater. There was no time to recall the 1st Battalion from Great Britain, or to create and train a new engineer battalion from scratch. Instead, the War Department ordered all personnel and equipment of the 29th Infantry Division’s 121st Engineers to move from Fort Meade to Fort Indiantown Gap to join with the 3 platoons from D, E and F Companies of the 112th Engineers. This new unit was designated the 117th Engineer Combat Battalion. Within this battalion, Companies A,B,C, HQ & Service plus a medical detachment were filled.

Orders were changed and the 37th was diverted for service from the European Theater to the Pacific Theater. There was no time to recall the 1st Battalion from Great Britain, or to create and train a new engineer battalion from scratch. Instead, the War Department ordered all personnel and equipment of the 29th Infantry Division’s 121st Engineers to move from Fort Meade to Fort Indiantown Gap to join with the 3 platoons from D, E and F Companies of the 112th Engineers. This new unit was designated the 117th Engineer Combat Battalion. Within this battalion, Companies A,B,C, HQ & Service plus a medical detachment were filled.

|

| 117th Co. C at San Francisco Port |

On April 10, 1942 the personnel assigned to 117th Engineers from 112th and 121st Engineers arrived at Indiantown Gap. Private First Class Sam Price was re-assigned from the 112th Engineer Battalion to Company “C” of this newly formed 117th Combat Engineering Battalion. After about a month of additional training, the 117th departed on May 8th by rail to Oakland, California and arrived on the afternoon of May 12th. Once in Oakland, the troops were quartered in the International Harvester building. They stayed there until getting orders on May 24th to report to the San Francisco Port for assignment overseas. That evening, Company C boarded the SS President Monroe (APA-104) and set sail across the vast Pacific Ocean as part of Task Force 6429.

It was finally revealed that the troops were steaming to New Zealand. On June 12th, the SS President Monroe arrived at Hauraki Harbor, New Zealand. Company C disembarked on the 13th at Auckland and traveled to Camp Hilldene. Here they held training exercises, conditioning marches, construction projects at the camp as well as build defensive positions. The Kiwis were overwhelmingly supportive and hospitable to these “Yanks” and welcomed them with open arms. On June 23rd, the company returned to Auckland, boarded the SS President Coolidge and got under way two days later bound for the island of Fiji.

The Coolidge arrived at Suva Harbor, Fiji on June 28th. The Engineers disembarked the following day and traveled 175 miles by truck to Lautoka. The 37th Division had been sent there to fortify the island against a possible Japanese invasion. The 117th Engineers were tasked to repair and improve roadways and bridges, construct facilities for the division area and train in combat team situations. While Sam was stationed in Fiji, his mother Anna joined the Mt. Ephraim Selectees’ Mothers Club on October 1, 1942.

The Selectees’ Mothers Club, Chapter XI, of Mount Ephraim was organized in 1942. This club hosted card parties to raise funds for cash gifts to send to each serviceman. Any military member without a relative in this organization was given "adopted parents" to sponsor them. The Selectees’ Mothers planned and oversaw the construction of an honor roll which displayed the names of those residents of the borough who were serving in the military. They would also be responsible for the purchase and dedication of the town's World War II monument in which Price’s name is engraved.

Sam was awarded $3 by Selectees Mothers on November 7th, 1942 and again December 5th. On December 17th, the club gifted him with another five dollars. For the December 5th drawing, all the names were picked by a young Ronnie Dye, the little brother of navy airman Jimmy Dye. Jimmy would later be captured and executed at the hands of the Japanese.

Sam was awarded $3 by Selectees Mothers on November 7th, 1942 and again December 5th. On December 17th, the club gifted him with another five dollars. For the December 5th drawing, all the names were picked by a young Ronnie Dye, the little brother of navy airman Jimmy Dye. Jimmy would later be captured and executed at the hands of the Japanese.

The 117th Engineers departed Fiji on April 17, 1943 and arrived 4 days later at their next destination, the now famed Guadalcanal in the Solomon Islands. "Higgins" boats transferred Company C and their equipment to the beach. The 37th Infantry Division had arrived after the brutal battle that the Marines fought here from August 7, 1942 until the beginning of February 1943. The engineers went to work right away clearing dense brush, constructing roadways, improving infrastructure and later training on various facets of carpentry, rigging, electricity, general mechanics and demolition.

Sam's company received orders in late May to deploy to Banika, Russell Islands with the 148th Regiment Combat Team. On May 31, they were transported by ship to the small island located 30 miles northwest of Guadalcanal. The engineers constructed incinerators, tin can pits and worked to resolve the lack of sufficient potable water for the growing number of troops on the island. Sam was awarded a $3 gift on June 3rd courtesy of the Mount Ephraim Selectees’ Mothers Club. At some point while overseas, Sam was promoted to Technician Fifth Grade (Tec-5). This rank was equivalent to a Corporal.

|

| 117th Engineer Bulldozer |

A small group of 117th Engineers consisting of 2 water section men and 2 bulldozer operators from Company C arrived ahead of the rest of the division. These engineers quickly set up water purification equipment and cut supply trails through the thick jungle. Enemy snipers shot at the bulldozers, trying to disable the equipment and delaying allied infantry advancement. On this day, the 2 engineers from Company C were shot, killing one and wounded the other while operating the dozers.

On July 23rd, LST-339 (Landing Ship, Tank) arrived at Rendova, Solomon Islands from Banika with the remainder of Company C, 117th Engineers. Rendova was a small island situated just south of New Georgia. It was utilized as an allied staging point for the Battle of Munda Point which took place from July 21 to August 6, 1943. On July 26th, Company C was transported from Rendova to mainland of New Georgia.

New orders came 4 days later for the 117th Engineers to assist in clearing enemy positions along the trail utilized by the 148th Infantry Regiment. Japanese soldiers ambushed American vehicles as they drove much needed supplies to forward positions. By August 6th, the Munda Airfield was captured by allied forces. As enemy resistance throughout the island was eliminated, the 117th continued building new roadways and improving existing ones. Later in the month, they constructed a kitchen and mess hall for the Corp Headquarters as well as an exchange building for the Corp Signal Company.

New orders came 4 days later for the 117th Engineers to assist in clearing enemy positions along the trail utilized by the 148th Infantry Regiment. Japanese soldiers ambushed American vehicles as they drove much needed supplies to forward positions. By August 6th, the Munda Airfield was captured by allied forces. As enemy resistance throughout the island was eliminated, the 117th continued building new roadways and improving existing ones. Later in the month, they constructed a kitchen and mess hall for the Corp Headquarters as well as an exchange building for the Corp Signal Company.

By the evening of September 27th, the 117th Engineers departed New Georgia and returned to Guadalcanal the next afternoon. They moved into an area one mile west of the Matanikau River. Up to October 9th, the 117th constructed camp here. Each company cleared their own area, erected tent frames, mess halls, showers and volleyball courts. A battalion drill field and amphitheater were also built.

On October 11th, training began in earnest for the 117th. They would trained daily for 5 hours on procedures of engineer working party protection, bivouac defense, installation of mine fields, booby traps, construction of floating bridges, demolition plus individual, squad and platoon tactics, night operations and marching. The engineers also performed their regular tasks such as construction of a trash dumps, a PX (Post Exchange-Store), pistol range, warehouses and maintenance of roadways.

Each man was required to participate in different competitive games each afternoon (like volleyball or baseball). Frequent show-down inspections and inventories were taken to determine all shortages of equipment and supplies and were covered immediately by requisition. A Battalion pass in review was held on October 30th before Major General Robert S. Beightler, Commander of the 37th Infantry Division. On this day, Purple hearts awarded to 117th Engineers injured or killed.

Each man was required to participate in different competitive games each afternoon (like volleyball or baseball). Frequent show-down inspections and inventories were taken to determine all shortages of equipment and supplies and were covered immediately by requisition. A Battalion pass in review was held on October 30th before Major General Robert S. Beightler, Commander of the 37th Infantry Division. On this day, Purple hearts awarded to 117th Engineers injured or killed.

The 37th Division embarked upon their next mission, “Operation Cherryblossom” in early November 1943. Sam's company made preparations for movement on the first few days of the month, loading onto transport ships at Lunga Beach. On November 7th, they departed Guadalcanal for a 350 mile journey to the island of Bougainville, Papua New Guinea. The ships arrived at Empress Augusta Bay the next morning.

The 117th Engineers joined with the I Marine Amphibious Corps establishing and expanding the beachhead sector at Empress Augusta Bay. The engineers constructed supply roads, water points, bridges and airstrips. They engaged in extensive patrol activity as well. One such patrol mentioned in the 117th Engineer History was as follows: A patrol consisting of Captain Thomas P. Love, Lt. Stanley B. Ledford, Corporals Stephen M. Marquardt, Samuel J. Price, and a Private Moore contacted an entrenched Japanese patrol, one soldier sitting in the open was shot by Captain Love.

The 117th Engineers joined with the I Marine Amphibious Corps establishing and expanding the beachhead sector at Empress Augusta Bay. The engineers constructed supply roads, water points, bridges and airstrips. They engaged in extensive patrol activity as well. One such patrol mentioned in the 117th Engineer History was as follows: A patrol consisting of Captain Thomas P. Love, Lt. Stanley B. Ledford, Corporals Stephen M. Marquardt, Samuel J. Price, and a Private Moore contacted an entrenched Japanese patrol, one soldier sitting in the open was shot by Captain Love.

Many tales of rapid construction came from these parts, but the tale of "Lt. Rainey’s Road" topped them all. Early one morning, an infantry party surveyed the one mile stretch behind the 1st Battalion of the 148th Infantry Regiment, over a poor “peep trail” for the purposes of establishing defensive positions. The working parties appeared at noon to commence stringing barbed wire, but found the sketch to be lacking in one particular detail. The infantry lieutenant was severely reprimanded for not sketching the two-lane, all traffic road extending the full length of the sector. The lieutenant pleaded, “But there was no road there this morning!” He was correct. Sam's company were the responsible party who quickly created this roadway.

|

| 117th Engineer road construction |

From March 9th to April 3rd, the 117th Engineers dropped their shovels and took up arms. They were mostly used as reserves for the infantry but on several occasions, had to occupy positions up at the front. On one such instance, a small group of members from the 117th had orders to demolish an enemy pillbox on March 10th. As the group was pushing sections of bangalore torpedoes towards their objective, the demolition prematurely exploded, killing 4 engineers and wounding 4 more. After hostilities ceased, the 117th Engineers held a 2nd anniversary dinner on April 10, 1944. General Beightler and the commanding officers of the 37th Infantry Division were in attendance. The Battalion was later presented with a citation on June 10th for outstanding work accomplished in Northern Solomon Islands campaign.

Company C Engineers joined with the 145th Infantry Regiment for amphibious training from July 19th to August 24, 1944. On August 17th, the troops reported to LCI(L)-955 (Landing Craft, Infantry) at Empress Augusta Bay where they rehearsed amphibious landings on the area beaches throughout the day. Corporal Price would receive a $3 gift from the Mt. Ephraim Selectees’ Mothers Club on July 23rd and once again on October 5th.

117th commanders received word in the fall that the 37th Infantry Division would be called upon for another operation in the near future. Company C trained with 148th Infantry Regiment in laying and removing mine fields, demolition tactics, chemical warfare, bridge construction and engineer-infantry assault tactics. During this training, tanks, flame throwers, bangalore torpedoes, and live ammunition was used to make a very realistic and instructive program. Rifle marksmanship was practiced an hour each day for two weeks.

With all the intensive training going on, the men knew something was up. There was much speculation about their next destination — was it China? Burma? Borneo? Sumatra? Malay? Java? Realistically, the answer was anywhere except for home. “Tokyo Rose,” the Japanese propaganda radio personality helped dispel the rumors during a broadcast one day, stating that “The 37th Division would soon be leaving Bougainville for the Philippine Islands and they would never reach their destination.” Turns out she was correct in one aspect. They indeed were heading to the Philippines, but despite what she said, they would in fact arrive at their destination without being annihilated.

On December 2, 1944, Sam and his company boarded a transport ship at Empress Augusta Bay and departed on December 15th. The ship headed for the Huon Gulf, Papua New Guinea for additional training. Three days later, they arrived at Lae in Papua New Guinea, where they practiced amphibious landings for a few days. The group then departed for Admiralty Islands on December 20th. One day later, the ships arrived at Manus, Papua New Guinea. They stayed anchored here in Seeadler Harbor for almost a week. The 117th Engineer Battalion celebrated Christmas dinner aboard the ships. Personnel were given the opportunity to go ashore for an afternoon’s recreation, where each man was issued 4 bottles of beer.

The ships left Manus Harbor bound for the Philippine Islands on December 27th. The rest of the task group rendezvoused en route. This was a massive armada to behold. Naval vessels of all shapes and sizes including battleships, cruisers, escorts and carrier vessels stretched out across the horizon as far as the eye could see. The ships received some extra protection from above with fighter planes keeping a keen eye out for the Japanese Navy. The 117th Engineer History noted, “Nothing looked so good nor helped morale as much as seeing American planes overhead covering the convoy. It gave one a feeling of security.” The other thing the fly boys looked out for were the Japanese suicide planes, known as Kamikaze. They would deliberately crash their aircraft into allied ships. While en route to the Philippines, the convoy would have their first experience with the Kamikaze.

|

| 117th Engineers land at Lingayen Gulf |

Immediately upon disembarkation, Sam’s company developed a road through mushy ground along fish ponds and rice fields in order to bypass a damaged bridge in San Lupis. The next mission was to fix the Calmay River Bridge which Japanese soldiers had blown up to slow the advancing Americans. The engineers set up a “Bailey Bridge” (portable, pre-built truss bridge) across the damaged span to quickly get supplies moving into the area. Next was to repair the 120 foot-long Toroyo River Bridge on San Carlos Road. The company had this up and running by January 13th followed by construction of a timber bridge at Bilad on the 17th.

The 37th Infantry Division began its movement down Highway 3 with the 148th Infantry Regiment leading the column. General MacArthur and Major General Beightler encountered one another on the highway, where MacArthur conveyed to Beightler that he wished to see the 37th Infantry Division take Manila first. This was a remnant of the old bond Beightler and MacArthur shared from their World War I days with the Rainbow Division (42nd Infantry Division). Ultimately, they would not be the first to reach the city, as there were so many destroyed bridges that lay ahead of their forward progress.

Company C Engineers sent out a six jeep recon party to “peep” the enemy on January 25th. They were ambushed at a roadblock west of Malabacat but were able to escape without receiving any casualties. They continued onto Santa Maria, where they were ambushed once again by Japanese tanks. This time, the men had to abandon their vehicles after the jeeps became bogged down and had to withdraw on foot, six miles back to the American line. Several men were injured from this attack. The more seriously wounded men were hidden in ditches and covered with grass and leaves until they could be evacuated later that day. The men would move on to Magalang two days later, to repair a secondary road with the 148th Infantry Regiment.

The next objective was the seizure of Plaridel, a city twenty miles north of Manila at the merging of Highways 3 and 5. The 37th Infantry Division reached Plaridel where they encountered an entrenched Japanese garrison. The division overcame their first experience with street combat with relative ease; however, their advance was halted at the Pampanga River. The 117th Engineers were not provided with enough bridging material to span the river. This forced the Battalion to improvise.

By the evening of February 3rd, while in the area of Bocaue, Sam and company gathered all available explosives and moved out towards Manila for any demolition work that might be needed.

Company C had traveled on foot, reconnoitering sites, improving crossings and doing everything possible to keep light vehicles up with forward elements of the infantry.

Some reconnaissance teams went out in the morning, headed for Manila. They only got as far as the Balintawak Beer Brewery on the outskirts of the city. For some reason they were waylaid there and couldn’t go on. It was reported that there was “FREE BEER,” and all that was needed was some kind of container.

|

| Guard duty at the brewery |

Buckeye Division member Frank Mathias remembered, “As we neared, we saw a scene unique in the annals of the bejungled Pacific War. Soldiers were sloshing helmets full of beer over their heads and any other heads nearby.” A soldier uses his helmet for every conceivable use -- wash basin, cooking utensil, and in drastic cases, a lavatory. However, this is the first time in history of the 37th Division that they were used as a beer mug.

|

| G.I.s filling up containers with beer |

Since hitting the beaches at Lingayen, the 117th Engineers had built 5 timber trestle bridges, repaired 28 bridges, reconstructed 6 bridges and installed 12 pre-fabricated spans such as pontoon, Bailey, treadway bridges and infantry support rafts. It was said that a small bridge or culvert was rebuilt every couple of miles and at least one large bridge every ten to fifteen miles.

While bridge and roadway repair was the primary duty of the Buckeye Engineers, the battalion was also responsible for successfully removing more than 1,300 land mines over a three-day period at Fort Stotsenberg and Clark Army Airfield. Additionally, the men set-up and operated water purification systems. With all these accomplishments under their belt so far, the work was far from over. During the final push from Angeles to Manila, the engineers faced ten additional river crossings with demolished bridges in which to overcome.

As the 37th Infantry Division prepared to enter Manila they were greeted with near constant artillery and mortar fire while Japanese rockets screeched overhead – a new weapon encountered by the GIs. The Buckeyes possessed excellent artillery; however, orders from General MacArthur, who wanted to limit infrastructure damage to Manila, severely limited its use. The Guardsmen looked on helplessly at night as the sky glowed from the illumination of burning buildings – it was apparent the Japanese intended to destroy the city.

It was not until February 7th that the winds shifted so that the fires were reduced enough for the infantry to advance. The first divisional unit to enter the heart of Manila was the 117th Engineer Battalion, attached to the 148th Infantry Regiment, through the Santa Cruz District.

While bridge and roadway repair was the primary duty of the Buckeye Engineers, the battalion was also responsible for successfully removing more than 1,300 land mines over a three-day period at Fort Stotsenberg and Clark Army Airfield. Additionally, the men set-up and operated water purification systems. With all these accomplishments under their belt so far, the work was far from over. During the final push from Angeles to Manila, the engineers faced ten additional river crossings with demolished bridges in which to overcome.

As the 37th Infantry Division prepared to enter Manila they were greeted with near constant artillery and mortar fire while Japanese rockets screeched overhead – a new weapon encountered by the GIs. The Buckeyes possessed excellent artillery; however, orders from General MacArthur, who wanted to limit infrastructure damage to Manila, severely limited its use. The Guardsmen looked on helplessly at night as the sky glowed from the illumination of burning buildings – it was apparent the Japanese intended to destroy the city.

It was not until February 7th that the winds shifted so that the fires were reduced enough for the infantry to advance. The first divisional unit to enter the heart of Manila was the 117th Engineer Battalion, attached to the 148th Infantry Regiment, through the Santa Cruz District.

Parties made numerous attempts throughout the day to find suitable crossings but due to intense enemy fire, the reconnaissance could not be completed. At 12pm, the engineers were instructed to support the 148th Infantry Regiment in the assault crossing set for 2pm. The site of the crossing, selected by the infantry was to be in the vicinity of the Malacañan Presidential Palace in San Miguel.

The 3rd Battalion of the 148th Infantry Regiment led the assault across the Pasig River to the Malacañan Gardens, a botanical park located on the shore opposite the palace. By 2pm, thirty assault boats had been delivered to the crossing site and ready for launching.

|

| 117th Eng & 37 Inf. Div. soldiers crossing the Pasig River |

Sam's company began shuttling soldiers from the 129th Infantry Regiment across the river on February 8th. The soldiers headed west towards Provisor Island after disembarking at the grounds of the Malacañan Gardens. This island, only 25 yards from the park was a key electric generating facility for the city. It was now being utilized as a Japanese defensive strongpoint. Provisor Island is about 400 yards long and 125 wide. It is bordered to the north by the Pasig River, Estero de Tonque to the east, and Estero Provisor to the west and south.

One of the 129th Infantry Regiment companies attempted to cross the Estero de Tonque on the eastern end of the island. They were spotted by Japanese Marines, who quickly began targeting them with mortars and machine gun fire. The American infantrymen were pinned down and the operation was called off for the evening. A new plan was devised to have artillery fire directed at the island, ahead of the infantry for the next morning.

The engineers were preparing to continue the ferrying operations on the warm and clear morning of February 9th. Their mission was to transport elements of the 129th Infantry Regiment, Company G across the mouth of the Estero de Tonque on the Pasig River utilizing only two wood and rubber assault boats. The mission of the infantry was to seize the boiler plant located on the northeast corner of Provisor Island.

The first boat, helmed by engineers Tec-5 Charles C. Talbott and PFC Ralph E. True, managed to get across with eight soldiers from Company G, but all had to scramble ashore, leaving the boat in the water to drift away.

|

| Antonio Guevara |

William and Anna Price wouldn’t receive word of Sam’s death until around March 11th or 12th. The announcement of his death was finally reported in the Courier-Post on March 13th.

Memorial Day services were held in Mt. Ephraim on Sunday, May 27, 1945 at the borough’s World War II Honor Roll located at Black Horse Pike and Kings Highway — the present location of the gas station. This somber event honored 10 servicemen from town who made the ultimate sacrifice as well as 375 other men and women still serving in the armed forces. At the conclusion of the ceremonies, Sam’s parents placed a wreath at the base of the honor roll in memory of their son.

When the war was over, Sam's remains were exhumed and transferred to Crypt #27 at the American Graves Registration Services Mausoleum in Manila. In 1948, the War Department sent a letter to the Price Family inquiring about the wishes of the burial location of their son. The decision was made to bring Sam back home to New Jersey.

Corporal Price was shipped back to San Francisco aboard an Army transit and then transported across country with a military escort. The services were held on the morning of June 26, 1948 at Foster’s Funeral Home in Audubon, NJ. A procession made its way from Audubon to Lakeview Memorial Park in Cinnaminson, NJ for interment where military rites were performed by the Mount Ephraim V.F.W. Post 6262. Sam was posthumously awarded with the Purple Heart, the Philippines Liberation Medal and a Distinguished Unit Citation received by the 117th Engineers for outstanding actions taken in Luzon from January 9 to March 3, 1945.

|

| Sam's gravesite, Memorial Day 2019 |

“They say time heals all sorrow

And helps us to forget.

But time so far has only proved

How much we miss him yet.

God gave us strength to fight it,

And courage to bear the blow.

But what it meant to lose our Sam,

May their sacrifice never be forgotten.

Comments

Post a Comment